In 1978, one of the finest minds of the 20th century, philosopher, historian and scientist James Burke, wrote and presented a television series called Connections; An alternative view of change. As a teenager I watched this avidly because it showed me a new approach to history. History is not a linear, neatly packaged process the way it is often taught. Random events conspire to affect change. People work motivated by their own reasons, often to solve a particular problem or to make a profit. Earlier work is improved upon or provides a stimulus to become something entirely different. To trace a path through the development of anything can take you to some very surprising places, seemingly unconnected until you understand how you got there. This was a revelation, one for which I have been grateful my entire adult life. In short, the series taught me how to think.

In 1978, one of the finest minds of the 20th century, philosopher, historian and scientist James Burke, wrote and presented a television series called Connections; An alternative view of change. As a teenager I watched this avidly because it showed me a new approach to history. History is not a linear, neatly packaged process the way it is often taught. Random events conspire to affect change. People work motivated by their own reasons, often to solve a particular problem or to make a profit. Earlier work is improved upon or provides a stimulus to become something entirely different. To trace a path through the development of anything can take you to some very surprising places, seemingly unconnected until you understand how you got there. This was a revelation, one for which I have been grateful my entire adult life. In short, the series taught me how to think.

At the end of the penultimate episode of Connections, James Burke explains why he believes history to be so important to humanity, a theme he expands on in the final part. It is a very simple but vital message: “You can only know where you are going, if you know where you have been.” Producing this issue has taught me one thing, the message of Connections could be the motto of Alenia Aermacchi.

This is a company with strong roots, having grown into an international aerospace giant over the last 100 years while staying in the same area. It has produced extraordinary, world beating aircraft throughout its history, and I was astounded and ashamed to discover how few I knew anything about and how much I still have left to learn, not only about the aircraft, but also the talents that created them. That shame has now turned to delight as the full picture emerged from my research.

The people behind this story are almost a family, the developments they began interweaving through the various companies in a complex series of relationships. Sometimes the co-operation between the companies was officially frowned upon, the work of Mario Castoldi at Macchi and Tranquillo Zerbi at Fiat was based upon Castoldi’s need for powerful racing engines, work they carried out often at an unofficial personal level. Test pilots, engineers and scientists you would expect to find in this story, but this period of racing development was initiated by a French industrialist who wanted to connect the great seaports of the world with commercial flying boats. The international competition he financed was instead to affect the development of high performance aircraft for the Second World War. Like I said earlier, history does not conform to neat packages. The century behind Alenia Aermacchi travels a varied and fascinating road. It takes it from companies that produced railway rolling stock, gun limbers and wagon wheels to two companies that still produce modern luxury yachts and then into space.

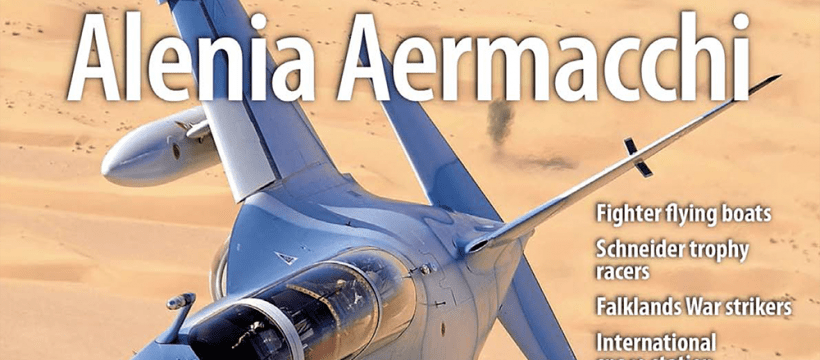

All through this story one factor in the success of Alenia Aermacchi is prevalent, its sense of its own heritage. The company began with military and commercial aircraft, but it is high performance – yet cost effective – trainers that have formed the keystone for 60 years at Aermacchi, a development chain that has resulted in today’s superb M.346.

Fiat, through to Aeritalia and Alenia have been at the cutting edge of combat aircraft development for decades, a line that culminates in the Typhoon and shortly the F-35. From my research, I feel it is an appreciation and an understanding of the value of its legacy that has brought the group such international success. The photographs on these pages feature a collection of the aircraft on display at the Venegono factory complex, along with one of its most famous products recently returned to flight. Clearly, this is a company which knows where it has been. What will be just as fascinating is where this solid foundation of knowledge will take it in the next 100 years.

Happy 100th birthday Alenia Aermacchi!

As usual, I have been assisted in the production of this magazine by some remarkable and enthusiastic people. Aviation Classics’ old friend Colonel Douglas C Dildy has been joined by Santiago Rivas and Lewis Mejía in explaining the use of the MB.326 and 339 in Argentina and Peru, Colonel Dildy adding to his history of the aircraft of the Falklands War following on from the Harrier and Mirage issues. Another old friend, Luigino Caliaro, waited in the rain and fog for weeks until the weather cleared just long enough to get the airborne photographs with the Vola Fenice MB.326. I would also like to thank the great Italian historian and aviation expert Gregory Alegi, who has supplied many fascinating insights into the people behind the aircraft, as well as vital information that clarified the histories of the smaller companies in the lineage. There has also been a tremendous amount of support from Alenia Aermacchi itself, and I would like to record my deepest appreciation for the efforts of Marco Valerio Bonelli, Barbara Buzio and Bruno Frigerio who between them supplied many of the images that grace these pages, not to mention a great deal of information.

As usual, I have been assisted in the production of this magazine by some remarkable and enthusiastic people. Aviation Classics’ old friend Colonel Douglas C Dildy has been joined by Santiago Rivas and Lewis Mejía in explaining the use of the MB.326 and 339 in Argentina and Peru, Colonel Dildy adding to his history of the aircraft of the Falklands War following on from the Harrier and Mirage issues. Another old friend, Luigino Caliaro, waited in the rain and fog for weeks until the weather cleared just long enough to get the airborne photographs with the Vola Fenice MB.326. I would also like to thank the great Italian historian and aviation expert Gregory Alegi, who has supplied many fascinating insights into the people behind the aircraft, as well as vital information that clarified the histories of the smaller companies in the lineage. There has also been a tremendous amount of support from Alenia Aermacchi itself, and I would like to record my deepest appreciation for the efforts of Marco Valerio Bonelli, Barbara Buzio and Bruno Frigerio who between them supplied many of the images that grace these pages, not to mention a great deal of information.

To you all, if you will forgive my lack of your beautiful language, molto molte grazie.

All best,

Tim

Contents

Contents

8 The genesis of Alenia Aermacchi

10 Giulio Macchi

14 First World War – The companies are founded

30 Inter-war years

52 The great race – The Schneider Trophy

62 The Second World War

70 Postwar rebuilding

80 Jet success

90 Flagship trainer

96 Over the Falklands

104 International programmes and consolidation

120 Into the 21st Century

122 Limited edition prints

124 Survivors

129 Subscribe

130 Next month

International programmes and consolidation

With the creation of Aeritalia in 1969, Fiat owned a 50% share of a powerful and experienced aerospace manufacturer. This was to find success in international programmes such as the Panavia Tornado and Boeing 767, but was also to produce the last design led by Giuseppe Gabrielli, the G.222 twin turboprop transport.

With the creation of Aeritalia in 1969, Fiat owned a 50% share of a powerful and experienced aerospace manufacturer. This was to find success in international programmes such as the Panavia Tornado and Boeing 767, but was also to produce the last design led by Giuseppe Gabrielli, the G.222 twin turboprop transport.

As discussed in Aviation Classics Issue 11 regarding the Hawker Siddeley Harrier, in 1962 NATO had issued two specifications for vertical and short take off and landing (V/STOL) aircraft, the second of these, NATO Basic Military Requirement 4 (NBMR-4) was aimed at acquiring a V/STOL transport. In response, Giuseppe Gabrelli’s design team had produced the original G.222 concept, powered by two Rolls-Royce Dart turboprops with between six and eight jet engines for vertical thrust. Even when the NATO project was cancelled, the Aeronautica Militare Italiana (AMI) remained interested in the aircraft as a tactical transport, ordering two prototypes in 1968.

The vertical flight capability had gone, the original Darts being replaced by a pair of General Electric T-64 turboprops, but the aircraft retained very short field capability through the use of high lift devices and a very efficient wing. The outer wing sections were designed and built by Aermacchi in another example of the close co-operation between the two companies. The prototype was first flown by Vittorio Sanseverino on July 19, 1970, the AMI testing the aircraft in December and issuing a contact for 44 to be built. By this time, Fiat Aviazione was part of Aeritalia, so this was not only the last Gabrielli designed aircraft, it was the last to be produced under Fiat and its designation system.

G.222 variants

The first G.222 entered AMI service in April 1978, its STOL performance meaning it could land in only 550m (1800ft) but its capacious cargo fuselage was capable of carrying 9000kg (19,840lb) of cargo or 53 fully equipped troops. Sometimes referred to as the twin engined Hercules, its rear ramp door design meant it could be loaded and unloaded quickly and deliver cargo by parachute drop. One aircraft was produced for the AMI as the G.222SAA, fitted with aerial firefighting equipment that could drop water or fire retardants, and two more were fitted with electronic countermeasures equipment as the G.222VS or GE as it is sometimes known.

The last variant for the AMI was the G.222RM, four of which were fitted with equipment to calibrate radar and radio ground stations. Of the 52 G.222s operated by the AMI, one RM and one VS variant are still in service, the rest were retired in 2005. Their 27 year service with the AMI was to include a great deal of humanitarian aid and support for the UN, particularly in Somalia and the Balkans during the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo during the 1990s. One G.222 was lost on September 3, 1992, when it was shot down by a ground launched missile on approach to Sarajevo airport while undertaking a UN relief mission.

The G.222 attracted a number of export orders, among them five for Tunisia, eight for Venzuela and one from Dubai. In 1977, 20 G.222s were ordered by Libya, but a US arms embargo meant they had to be re-engined with Rolls-Royce Tyne turboprops in which form they were known as G.222Ts. Two were delivered to the Somalia Air Corps and five to the Nigerian Air Force in 1984 and 1985; the latter has since also acquired an ex-AMI aircraft in 2008. The Royal Thai Air Force operated six G.222s until 2012, when they were retired. Argentina’s Army Aviation purchased three of the transport, which were in service at the time of the Falklands War, but were not used in that conflict and have since been withdrawn.

The USAF purchased 10 G.222s in 1990 as a rapid response airlifter, where the aircraft was known as the C-27A Spartan. These would later be replaced by the current version of the aircraft, the C-27J, which will be described later in this magazine. Four of the C-27As are now operated by the US State Department in anti-narcotic operations in South America from Patrick Air Force Base in Florida. In September 2008, the USAF contracted Alenia Aermacchi (as it had since become) to supply 18 refurbished ex-AMI G.222s to the Afghan National Army Air Force as transports with an additional two capable of being fitted as VIP transports.

The first was delivered on September 25, 2009, with 16 being supplied by December 2012. Sadly, by January 2013, despite massive training and technical support efforts from Alenia Aermacchi and the USAF, the contract was cancelled. This was due to in-country problems with maintenance and spares supplies caused by alleged corruption by Afghan government and air force officials. It appears that the aircraft will be scrapped or withdrawn, a sad end to the operational career of an excellent transport.

Consolidation

While the G.222 programme was going on, Fiat underwent a complete reorganisation in 1976, and at this point the famous Fiat name leaves the story of Alenia Aemacchi. The Fiat Aviazione Turin and Brindisi facilities went over to building only aero engines and drive systems, such as helicopter gearboxes. Fiat’s 50% share in Aeritalia, the aircraft production elements of the company, was sold to state owned IRI Finmeccanica. In 1989, the Fiat aero engine company was renamed Fiat Avio, acquiring Alfa Romeo Avio from Finmeccanica in 1997 to consolidate the Italian aero engine, rocket, drive train and engine management system industry. Fiat Avio works with Airbus, Boeing and Panavia among many others, developing engines and power delivery and management solutions for a wide range of civil and military aircraft.

The company formed European Launch Vehicle (ELV) to develop rockets for the European Space Agency and others in 2000, changing its name to Avio S.p.A in 2003. On December 21, 2012, US aero engine giant General Electric (GE) announced it was purchasing the aviation propulsion and management systems elements of the company, subject to government approvals, as Avio was already a partner in so many GE aero engine programmes. Due to its experience and success with rocket systems and launch vehicles such as the Ariane series and Vega, Avio’s subsidiary rocket manufacturer, ELV, is likely to remain independent.

To return to Aeritalia and indeed, the year it became that company, 1969. Aside from being renamed and reorganised, the company also became part of Panavia on March 26 that year. This was initially formed between Messerschmitt Bölkow Blohm (now EADS), the British Aircraft Corporation (now BAE Systems) and Aeritalia (now Alenia Aermacchi) to design and develop the new European Multi Role Combat Aircraft, later named Tornado. The aircraft design and manufacture was divided up between the partner nations, essentially the forward fuselage, fin and tailplane going to Britain, the rest of the fuselage to Germany and the wings to Italy. The RB.199 engine for the Tornado was split up the same way, with Turbo Union being formed in June 1970 between MTU in Germany, Rolls-Royce in Britain and Fiat Avio (now Avio) in Italy. With the aircraft agreed upon as a two seat low level strike aircraft, in September 1971, the three governments gave their go ahead to the project.

Tornado

The prototype Tornado first flew on August 14, 1974, at Manching in Germany, and was the first of 992 Tornadoes of all versions built by the three nations from that date. The Italian prototype made its first flight on December 5, 1975, at Aeritalia’s Turin facility, the first of 100 Tornado IDS (Interdictor Strike) versions of the aircraft delivered to the AMI. There were remarkably few problems encountered with the aircraft in trials, considering the complex nature of the aircraft and its systems, especially the active control technology embodied in its computer governed digital flight control system.

The AMI received its first Tornado on September 25, 1981, with a Tri-national Tornado Training Establishment (TTTE) being formed in Britain at RAF Cottesmore that year to train crews from all three partner air forces, a process that was to continue until 1999. The production lines delivered the last aircraft in 1998, this being one for the only export customer for the Tornado, Saudi Arabia.

Aside from the 100 Tornado IDS aircraft already mentioned, the AMI operated two other types of the Tornado. The first of these was the Tornado ECR, 16 of the AMI’s Tornado IDS aircraft being converted to the electronic combat and reconnaissance version, with the first delivered on February 27, 1998. The Tornado ECR has additional sensors to detect and locate ground radars and can carry the AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missile to attack those radar sites. These are known as Suppression of Enemy Air Defences (SEAD) missions and often go under the interesting nickname of Wild Weasel, an old US Air Force term for the mission.

To perform reconnaissance missions, the AMI Tornado ECRs can also carry the RecceLite reconnaissance pod. The last version of the Tornado operated by the AMI was the air defence variant or Tornado ADV, originally developed only for Britain’s Royal Air Force but later also exported to Saudi Arabia along with the IDS variant. On November 17, 1993, the AMI signed an agreement with the RAF to lease 24 Tornado F3 fighter versions of the aircraft for 10 years. This was to fill the gap between the F-104S leaving service and the entry of the Eurofighter Typhoon, then expected in 2000. These aircraft served with the AMI until December 2004, with one being retained for the AMI Museum, the rest being returned to the UK. A batch of 35 F-16s leased from the US Air Force replaced them in the AMI until the Typhoon was fully ready.

On operations

The AMI’s Tornado fleet saw a great deal of operational use. In 1991, eight aircraft were deployed to take part in the Gulf War as part of the coalition forces. One was shot down but the crew ejected safely. During Operation Allied Force over Kosovo in 1999, 22 Tornado IDS and ECRs were deployed as bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. As a result of these experiences, in July 2002, 18 AMI Tornado IDSs were upgraded with GPS and laser inertial navigation systems, as well as the ability to carry the Storm Shadow cruise missile, Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) and the Paveway III laser guided bomb.

Four Tornado IDS were sent to Afghanistan in 2010 as part of the Italian military commitment there, and both the IDS and ECR versions were used during the intervention missions over Libya in 2011. Prior to this last deployment, in 2010 it was decided that the Tornado IDS would be the subject of a major upgrade and life extension programme to keep the aircraft in service until 2025. New digital cockpit displays, night vision goggles and new digital communications capabilities for tactical information sharing are all part of this upgrade.

Aeritalia entered into one other major international aircraft development programme shortly after it was formed. Along with the Civil Transport Development Corporation (CTDC), a consortium of Japanese aerospace companies, in 1972 Aeritalia joined Boeing in signing a risk sharing agreement to develop a new wide bodied twin engined airliner, a concept that would later become the Boeing 767. Aeritalia would produce all of the control surfaces on the new aircraft, the rudder, elevators, ailerons and flaps, with other components being built in Japan before final assembly in the US at Boeing’s Everett factory in Washington. The first Boeing 767 flew on September 26, 1981, and to date six airliner variants have been produced with differing capacities and ranges.

The 767 airframe has also been adapted as a airborne early warning and control aircraft (AWACS) for the Japanese Self Defence Forces (JSDF) as the E-767 and as the KC-767 tanker transport, four of which have been produced for both the JSDF and AMI. Most recently, the KC-46A tanker transport version of the airframe won the US Air Force’s KC-X tanker competition, the contract for the first 18 of an expected 179 aircraft being awarded in February 2011. Up to March 2013, Boeing had built 1044 Boeing 767s against confirmed orders for 1108, a tremendous success for all the companies involved.

Officine Ferroviarie Meridionali and Industrie Aeronautiche Romeo

In engineering history, the name of Alfa Romeo will forever be associated with some of the fastest and most elegant cars ever built. What is less well known is that the name Romeo is also associated with railways and aircraft, a series of businesses all founded by one man – Nicola Romeo.

In engineering history, the name of Alfa Romeo will forever be associated with some of the fastest and most elegant cars ever built. What is less well known is that the name Romeo is also associated with railways and aircraft, a series of businesses all founded by one man – Nicola Romeo.

Nicola Romeo was born on April 28, 1876 in Sant’Antimo, the son of a primary school teacher. His father was to have a tremendous influence on his life as from an early age he ensured Romeo was well-versed in mathematics.

He worked his way through college to obtain a degree in engineering from the Technical University of Naples in 1899, moving to Liege in Belgium that year, where he graduated in electrical engineering. On his return to Italy he worked as a representative of Belgian industrial machinery companies, before founding the first of his own companies – Società in accomandita semplice Ing Nicola Romeo e Co (Ing Nicola Romeo and Co Ltd) – producing heavy mining equipment in 1905. This was extremely successful, especially in the production of compressed air systems and powered mining tools.

In 1915, Romeo bought the majority shareholding of the Anonima Lombarda Fabbrica Automobili (ALFA, the Lombardy Automobile Factory Company) taking over the directorship and overseeing the conversion of the factory to produce military vehicles, weapons and equipment for the First World War.

In 1918, at the end of the First World War, Romeo had bought the whole of the ALFA company, investing the profits he made back into his own company – Ing Nicola Romeo and Co Ltd. This grew and diversified with the acquisition of three factories producing railway locomotives and rolling stock: one in Rome, one in Saronno and the Officine Ferroviarie Meridionali (OFM or Southern Railway Workshops), which was situated in Naples. To reflect this, he changed the name of his holding company to Società anonima Ing Nicola Romeo e Co (Ing Nicola Romeo and Co Company) as it was now managing the mining, automobile and railway companies. In 1920, the ALFA company was renamed Alfa Romeo, the famous automobile manufacturer of which his name is most often associated.

At this time, Romeo was becoming interested in the possibilities of aviation, having seen the success of other companies. To achieve similar success, by 1923 he considered the OFM Naples railway factory and its workforce suitable as an aircraft producer. The first aircraft contracts were won from Fiat, to produce aircraft parts, and later the inverted sesquiplane Fiat CR.1 fighter under licence, as Fiat’s factories were fully employed with other projects. Considering what was to happen later in 1969, these Fiat contracts could be seen as a premonition of things to come.

A great deal of confusion exists regarding the use of the name Industrie Aeronautiche Romeo (IAR) in relation to aircraft production in Naples. Although this name was used occasionally, it was not an officially registered company name until 1934. However, the aircraft produced in Naples by OFM from 1925 onwards frequently carried the inscription Aeroplani Romeo painted somewhere on the airframe. All the aircraft built by the company were popularly known as both OFMs and Romeos, but all were given the designation prefix Ro.

In 1925, Romeo began negotiations with Fokker, in the Netherlands, to build its general purpose Fokker CV-E two-seat biplane. In 1926, a Romeo-owned aircraft factory was established in Pomigliano d’Arco, a province of Naples, under the OFM company.

The first completed CV-Es were built by OFM workers gaining vital experience in the Dutch Fokker factories late in 1926. These were modified with an improved undercarriage, ventral fin and provision for an observer’s machine gun on a flexible mount. In this form, known as the Romeo Ro.1, the first Naples-built versions rolled out of the new factory in March 1927. Given the nature of Romeo’s business interests, it is unsurprising that the engine was a 420hp Alfa Romeo Jupiter IV engine, built under licence from Bristol, in England.

Alfa Romeo was by now establishing a fine reputation for lightweight and powerful automobile engines designed by Vittorio Jano, so producing aircraft engines was a natural progression for the company within the Romeo group. However, by 1928, Nicola Romeo had left the Alfa Romeo automobile company to concentrate on his other concerns after financial difficulties had caused a division in the management. This was a tremendous first success for Romeo, with 330 being built, some of the later aircraft having a third seat provided between the pilot and observers’ cockpits.

In late 1927, an attempt was made to create a fighter version of the design by reducing the wingspan from 15.3m to 12.5m. Known as the Ro.1 ridotto (or reduced), this project remained as just a prototype. The improved version of the aircraft, the Ro.1bis, was powered by a 550hp Piaggio Jupiter VIII, fitted with a four-bladed propeller, of which 132 were built. The Ro.1s were to remain in frontline service until 1935, taking part in operations in Libya between 1924 and 1927, then again in the Cyrenaica region in 1931, and finally in the war in Ethiopia in 1935. After this, the type was steadily withdrawn to training units, mostly being retired by the outbreak of war in 1939. With the Ro.1 production line established, OFM turned its attention to its own first designs.

In response to an Italian Air Ministry specification for a light training and touring aircraft, issued in 1928, the company produced its next aircraft – the Ro.5, a two-seat parasol-winged monoplane. Almost every Italian aircraft manufacturer entered the competition, the aircraft being put forward for comparative trials in February 1929. Interestingly, there was no clear winner, 10 of the submitted projects being deemed to have met the requirement.

The Ro.5 was bought by a number of flying schools, clubs and private owners, as well as a batch being supplied to the Regia Aeronautica which used it as a basic trainer and liaison aircraft. A wide variety of engines were fitted to the aircraft, the majority being powered by the 85hp Walter Vega or the 80hp Fiat A.50 seven-cylinder radial. It was built in two versions, the standard open cockpit Ro.5 and the Ro.5bis, with an enclosure over the cockpits. This was developed still further into the Ro.6 with the addition of the 85hp version of the Fiat engine. 1929 was a busy year for the company; not only were the Ro.1 and 5 in production, but OFM then built its second Fokker design under licence, the Fokker F.VII/3m tri-motor 10-seat transport aircraft. This was a high-wing cabin monoplane and one of the most successful transport aircraft of the period, used by air forces and airlines across Europe and the US, setting many distance and speed records around the world.

Known as the Ro.10, three examples were built in Naples for the two airlines Avio Linee Italiane and Ala Littoria, powered by three 215hp Alfa Romeo Lynx seven-cylinder radial engines. Again, these were licence-built versions of a British engine, the Armstrong Siddeley Lynx. Also in 1929, OFM chief designer Alessandro Tonini, who had worked at Macchi on the flying boat fighter designs, suffered some serious health problems, so Romeo hired Giovanni Galasso to work as a designer at OFM.

Galasso had studied industrial and mechanical engineering at Turin Technical University before working at the Direzione Tecnica dell’Aviazione Militare (The Military Aviation Engineering Directorate, or DTAM) in Turin. He then moved into industry, joining first Ansaldo then Fiat, working on the Fiat AS.1 light aircraft among others.

In 1930, after only a year, Galasso was made head of the technical department at OFM, bringing a number of his former colleagues from Turin to Naples to form a new design team. The first aircraft was the Ro.25, a trainer built in single- and two-seat versions. Only the two prototypes were built in 1930, one of which was a seaplane.

This was followed later the same year by the Ro.26, a two-seat aerobatic biplane trainer which was built in small numbers, again as both a land and seaplane.

In 1932, Galasso developed the Ro.1 reconnaissance biplane design into the three-seat Ro.30, which made its first flight that year. Unusually, in this aircraft the pilot was seated in front of the wings, the observer in a glazed cabin between the wings and the gunner in an open cockpit behind them. The Ro.30 was built in two versions, powered by either the 530hp Alfa Romeo Mercurius (a licence-built Bristol Mercury IVS.2) or the Piaggio 126-RC35 Jupiter (a licence-built Bristol Jupiter) of the same power, both being nine-cylinder radial engines. Only a few Ro.30s were built, as it was quickly replaced in production by the Ro.37. As a side shoot to their powered aircraft developments, in 1933 OFM also designed and built the Ro.35, a single-seat glider with a wingspan of 14.5m. Only one of these was produced, and given the civilian registration I-ABBB, but little more is known about it.

To return to the Ro.37 development, this was to be the major next success for the company as 294 would eventually be built for the Regia Aeronautica. Again, designed under the leadership of Giovanni Galasso, the Ro.37 was a biplane two-seat light bomber and reconnaissance aircraft intended to replace the Ro.1 in service.

The prototype made its first flight on November 6, 1933 and was powered by the 600hp Fiat A.30 V-12 engine. It carried two Breda 7.7mm machine guns mounted in the nose and a third on a flexible mount in the rear cockpit. A bomb load of 180kg (397lb) could be carried either under fuselage racks or in a ventral magazine for small munitions.

The Ro.37bis replaced the Fiat engine with the 610hp Piaggio P.IX RC.40, a licence-built version of the Gnome-Rhone 9K Mistral nine-cylinder radial. Altogether 325 of this version of the aircraft were built, both for the Regia Aeronautica and the air forces of Afghanistan, Austria, Ecuador, Hungary, Spain and Uruguay. The largest of these overseas operators by far was Spain, who used 68 of the Ro.37bis between 1936 and 1945.

Aside from its use in the Spanish Civil War, the Ro.37 also saw operational use in the Second World War with the Regia Aeronautica, in both North Africa and the Balkans, but its vulnerability to modern fighters quickly curtailed the use of the type, the last having been withdrawn before Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943.

Although the numbers of Ro.37s built were impressive, the next Galasso design – the Ro.41 – was to surpass even this, with 743 being built. Originally conceived as an open cockpit biplane fighter, it was extremely manoeuvrable but underpowered and something of an obsolete concept for the time.

The prototype first flew at Capodichino airfield on June 16, 1934 in the hands of Niccolò Lana. This was followed by the second aircraft on January 31, 1935. It was tested by the Regia Aeronautica, which ordered 50, the first entering service in July. Powered by the Piaggio P.VII C.45 of 390hp, the fighter could achieve 320km/h (200 mph) and was armed with a pair of 7.7mm Breda machine guns. The Ro.41 was used operationally as a fighter, 28 serving in the Spanish Civil War as interceptors and as fighter bombers over Rhodes in the opening months of the Second World War. They were also used as night fighters over Tobruk in August 1940, but were quickly withdrawn as more modern types became available.

It was as a trainer that the Ro.41 excelled, its superb handling proving ideal in that role, with 30 of the two-seat variant being ordered in 1937. Eventually, 510 single-seat and 233 two- seat aircraft were to be produced, the majority serving as trainers.

The Ro.41 proved popular and reliable, so much so that it was the first aircraft ordered back into production after the Second World War, with Agusta building 12 single-seat and 13 two- seat aircraft under licence in 1946, which were used as military trainers until 1950. There was an improved version – the Ro.41bis – with a larger engine and shorter wingspan, a single example of which was produced in 1937, but such was the performance of the original that this failed to attract orders.

As production of the Ro.41 began in 1934, Nicola Romeo significantly changed the organisation of the company on October 27 by splitting the OFM railway workshop and the aircraft business, creating, or possibly just officially recognising the aviation company as Industrie Aeronautiche Romeo (IAR), a name which had been in common usage for some time.

Just after this split, on November 19, 1934, the first flight of the last design produced under the original management took place. This was the Ro.43 reconnaissance seaplane, which had been under development from the Ro.37 landplane since 1933. It was produced to a Regia Marina specification of that year for a catapult-launched reconnaissance aircraft for use on capital ships.

After comparative trials against other types, the Ro.43 was ordered into production in 1935, with more than 200 being built. The Ro.43 was powered by a 700hp Piaggio PX R nine-cylinder radial engine, which gave it a maximum speed of 300km/h (186mph), but this performance came at the cost of a lightweight structure. This caused structural and seaworthiness issues, particularly from damage caused when winching the aircraft back on to its launching vessel from the water. However, the type was to remain in service onboard ships until June 1942 taking part in some of the most important naval actions in the Mediterranean such as the battles of Calabria in July 1940 and Matapan in March 1941. After this, the Ro.43 was used as a coastal patrol aircraft until the armistice in September 1943.

The company was to change further in 1935 when OFM was sold to Società Italiana Ernesto Breda, a company that was founded in Milan in 1886 to produce railway equipment, but had diversified, beginning aircraft production in 1921.

Later, between 1935 and 1936, Romeo also sold IAR to Breda, which combined the two companies into a single organisation on October 1, 1936.

Giovanni Glasso remained as head of the design department of the new company, which was named Industrie Meccaniche e Aeronautiche Meridionali (Southern Mechanical and Aviation Industries), often shortened to Meridionali or IMAM. The aircraft produced by IMAM will be dealt with later in this magazine.

Nicola Romeo’s industrial successes had brought him many awards and national recognition in Italy. Among these, he had been invested as a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy on May 24, 1925, and in 1929 he was named a Senator of the Kingdom.

After the sales of his companies he moved to his home in Magreglio on Lake Como, where he died on August 15, 1938, aged 62.

The value of Romeo’s business and engineering contributions to European industry is incalculable, so it is particularly gratifying that his name lives on today in the excellent reputation of the Alfa Romeo car company.