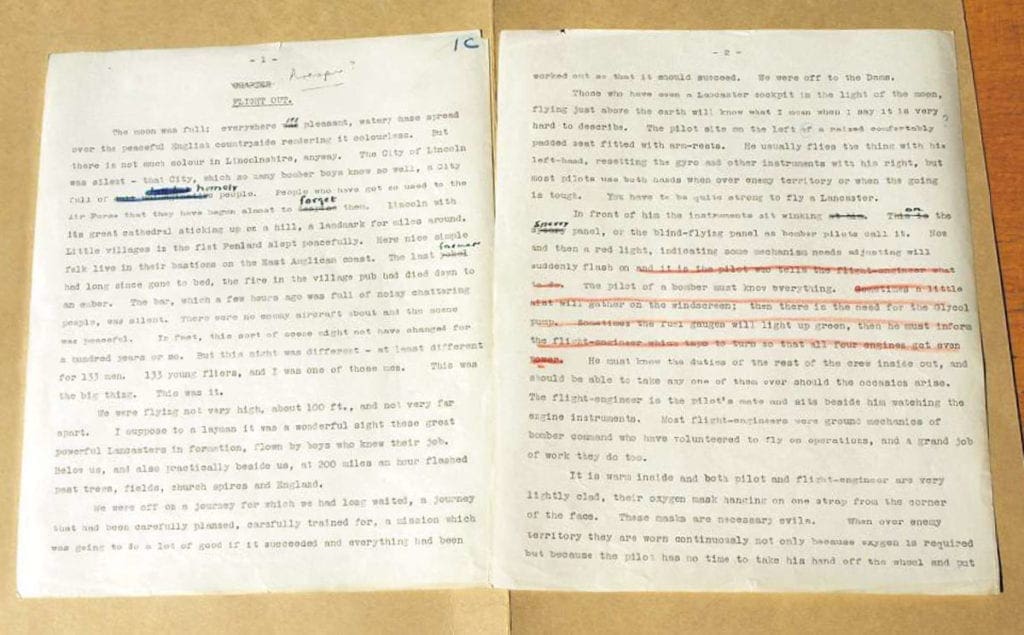

In 1944 Wg Cdr Guy Gibson VC DSO* DFC* wrote a fascinating account of his wartime experiences, which was first published in book form in 1946. What follows here are edited extracts taken from his original manuscript that form an article focusing on the famous Dams raid of 16/17 May 1943 – written by the man who formed and led 617 Squadron on this most famous aerial operation.

The moon was full; everywhere its pleasant watery haze spread over the peaceful English countryside, rendering it colourless. The city of Lincoln was silent – that city, which so many bomber boys know so well, a city full of homely people. People who have got so used to the Air Force that they have begun almost to forget them. Lincoln with its great Cathedral sticking up on a hill, a landmark for miles around.

Little villages in the flat Fenland slept peacefully. The last farmer had long since gone to bed, the fire in the village pub had died down to an ember. The bar, which a few hours ago was full of noisy chattering people, was silent. There were no enemy aircraft about and the scene was peaceful. But this night was different – at least different for 133 men: 133 young fliers, and I was one of those men. This was the big thing. This was it.

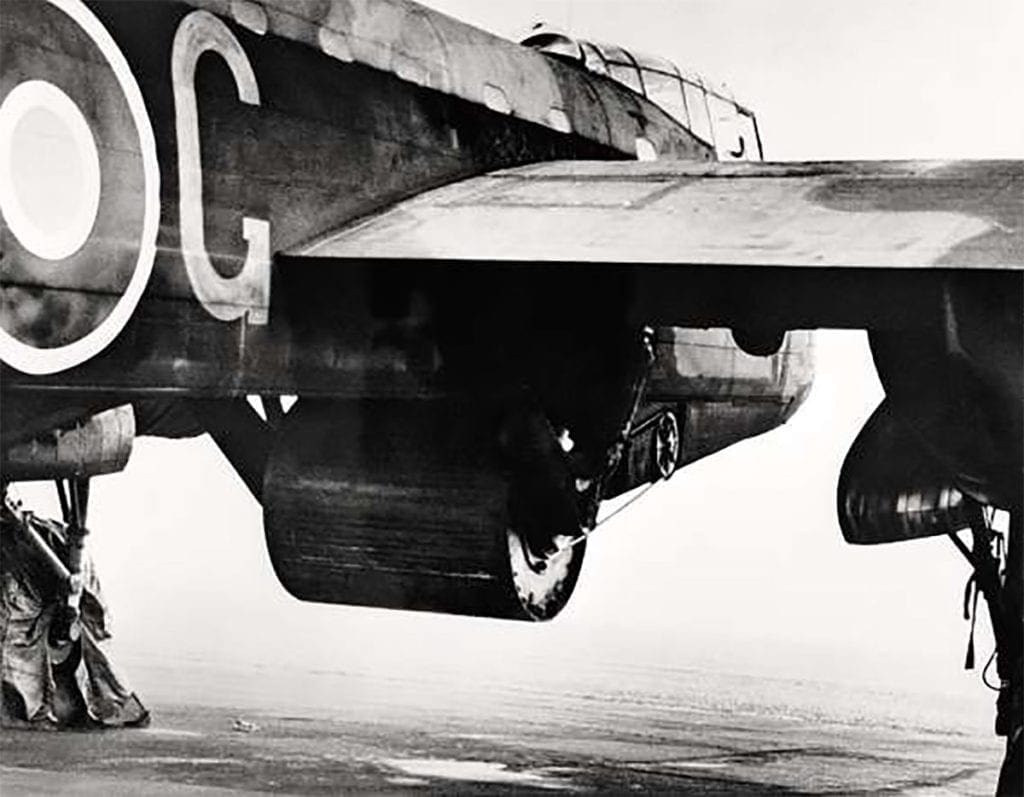

We were flying not very high, about 100ft, and not very far apart. I suppose to a layman it was a wonderful sight, these great powerful Lancasters in formation, flown by boys who knew their job. Below us, and also practically beside us, at 200 miles an hour flashed past trees, fields, church spires and England.

We were off on a journey for which we had long waited, a journey that had been carefully planned, carefully trained for, a mission which was going to do a lot of good if it succeeded, and everything had been worked out so that it should succeed. We were off to the Dams.

As I sat back in my comfortable seat, I could not help thinking that

Suddenly in the distance like a great arc

The sea was as flat as a

Then I settled down again but after

The night was so bright that it was possible to see the boys flying on each side quite clearly. The hours of darkness were limited, we had to go fast to get there and back in time.

One hour to go, one hour left before Germany, one hour of peace before flak. I thought to myself: here are 133 boys who have got an hour to live before going through hell. Some of them won’t get back. It won’t be me – you never think you are not coming back. We won’t all get back, but who is it will be unlucky out of these 133 men?

FIVE MINUTES TO GO

Terry spoke. We had been flying for about an hour and 10 minutes in complete silence – each one with his thoughts while the waves had been slopping by a few feet below us with monotonous regularity. And the moon dancing in those waves had become almost a hypnotising crystal. And as he spoke he jerked us into action. He said: “Five minutes to go to the Dutch coast, Skip.”

I said “Good,” and looked ahead trying to see if I could see anything. Pulford turned on the spotlights and told me to go down much lower; we were about 100 feet off the water. Jim Deering, in the front turret, began to swing it from either way ready to deal with any flak ships which might be watching for mine layers off the coast. Hutch sat in his wireless cabin ready to send a flak warning to the rest of the boys who might run into trouble behind us. Trevor took off his Mae West then squeezed himself back into the rear turret again.

Then Spam said: “There it is – there is the coast.” I said: “No, it’s not, that’s just low cloud and shadows on the sea from the moon.”

But he was right and I was wrong, and soon we could see the Dutch Islands approaching. They looked low and flat and evil in the full moon, squirting flak in many directions because their radar would now know we were coming. But we knew all about their defences and as we drew near this squat and unfriendly expanse, we began to look for the necessary landmarks which would indicate the ways and means of getting through that barrage; we began to behave like a ship threading its way through a minefield, danger of extermination on either side, but none if we were lucky and on track.

“Stand by front gunner, we’re going over.”

“OK. All lights off. No talking. Here we go.”

With a roar we hurtled over the Western Wall, skirting the defences, and turned this way and that to keep to our thin line of safety; for a moment we held our breath. Then I sighed a sigh of relief; no one had fired a shot. We had taken them by surprise.

We were flying so low that more than once Spam yelled at me to pull up quickly to avoid high tension wires and tall trees. It did not take Spam long to see where we were; now we were right on track and Terry again gave the new course for the river Rhine. A few minutes later we crossed the German frontier and Terry said in his matter-of-fact way:

“We’ll be at the target in an hour and a half. The next thing to see is the Rhine.”

As we flew along the Rhine, there were barges on the river equipped with quick-firing guns and they shot at us as we flew over, but our gunners gave back as good as they got; then we found what we wanted, a sort of small inland harbour and we turned slowly towards the east. Terry said monotonously: “Thirty minutes to go and we are there.”

As we passed on into the Ruhr Valley, we came to more and more trouble, for now we were in the outer light flak defences, and these were very active, but by weaving and jinking, we were able to escape most of them. Time and again searchlights would pick us up, but we were flying very low and although it may sound foolish and untrue when I say so, we avoided a great number of them by dodging behind the trees.

The minutes passed slowly as we all sweated on this summer’s night, sweated at working the controls and sweated with fear as we flew on. Every railway train, every hamlet and every bridge we passed was a potential danger, for our Lancasters were sitting targets at that height and speed. We fought our way past Dortmund, past Hamm, the well-known Hamm which has been bombed so many times; we could see it quite clearly now, its tall chimneys, factories and balloons capped by its umbrella of flak like a Christmas tree about five miles to our right. Then we began turning to the right in between Hamm and the little town of Soest where I nearly got shot down in 1940. Soest was sleepy now and did not open up, and out of the haze ahead appeared the Ruhr hills.

“We’re there,” said Spam.

“Thank God,” said I, feelingly.

And then, as we came over the hill, we saw the Möhne Lake. And then we saw the dam itself, and in the early light of the morning it looked squat and heavy and unconquerable; it looked great and solid in the moonlight as though part of the countryside itself and was never meant to be moved. A structure like a battleship was showering out flak all along its length, but some came from the power house below it and nearby.

There were no searchlights. It was light flak, mostly green, yellow and red, and the colours of the tracer reflected up on the face of the water in the lake; it reflected up on the dead calm of the black water so that, to us, it seemed there was twice as much as there really was.

“Did you say these gunners were out of practice?” asked Spam, sarcastically. “They certainly seem awake now,” said Terry.

They were awake all right. No matter what people say, the Germans certainly have a good warning system. I scowled to myself as I remembered telling the boys only an hour or so ago, there would probably only be a German equivalent of the Home Guard who would be in bed by the time we arrived.

It was hard to say exactly how many guns there were there, but tracers seemed to be coming from about five positions, probably making 12 guns in all. It was hard at first to tell the calibre of the shells, but after one of the boys had been hit, we were informed over the R.T. that they were either 20mm or 37mm type, which, as everyone knows, are nasty little things.

We circled around stealthily, picking up the various landmarks upon which we had planned our method of attack, making use of some and avoiding others; every time we came within range of those bloody-minded flak gunners, they let us have it.

“Bit aggressive, aren’t they?” said Trevor.

“Too right they are.”

I said to Terry: “God; this light flak gives me the creeps.”

“Me too,” someone answered.

TIME TO ATTACK

Down below, the Möhne Lake was as silent and black and deep as it ever was, and I spoke to my crew. “Well, boys, I suppose we had better start the ball rolling” – this with no enthusiasm whatsoever.

“Hello all Cooler aircraft. I am going to attack. Standby to come in to attack in your order when I tell you.”

Then to Hoppy – “Hello, ‘M Mother’, standby to take over if anything happens.”

Hoppy’s clear and casual voice came back. “OK, leader. Good luck.”

Then the boys dispersed to the prearranged hiding spots in the hills, so that they should not be seen either from the ground or from the air, and we began to get into position for our approach. We circled wide and came around down moon, over the high hills at the eastern end of the lake. On straightening up we began to dive towards the flat, ominous water two miles away. Over the front turret was the dam silhouetted against the haze of the Ruhr Valley. We could see the towers. We could see the sluices. We could see everything.

GIBSON’S CREW

| Pilot | Wg Cdr Guy Gibson DSO* DFC* |

| Flight engineer Navigator | Sgt J Pulford Plt Off HT Taerum (RCAF) |

| Wireless operator | Flt Lt REG Hutchinson DFC |

| Bomb aimer | Plt Off FM Spafford DFM (RAAF) |

| Front gunner | FS GA Deering (RCAF) |

| Rear gunner | Flt Lt RD Trevor-Roper DFM |

SOME OPERATION

CHASTISE CODE WORDS

| Target X | Möhne Dam |

| Target Y | Eder Dam |

| Target Z | Sorpe Dam |

| Cooler 1 | Gibson’s Lancaster |

| Goner | Special weapon released |

| Nigger | Target X breached |

| Dinghy | Target Y breached |

Spam, the bomb aimer, said: “Good show. This is wizard.” He had been a bit worried, as all bomb aimers are in case they cannot see their aiming points, but as we came in over the tall fir trees, his voice came up again rather quickly.

“You’re going to hit them. You’re going to hit those trees.”

“That’s all right Spam. I am just getting my height.”

To Terry – “Check height, Terry.”

To Pulford – “Speed control, flight engineer.”

To Trevor – “All guns ready, gunners.”

To Spam – “Coming up, Spam.”

Terry turned on the spotlights and began giving directions – “Down – Down – Down – Steady – Steady.” We were then exactly 60 feet.

Pulford began working the speed; first, he put on a little flap to slow us down, then he opened the throttles to get the air speed indicator exactly against the red mark. Spam began lining up his sights against the towers. He had turned the fusing switches to the ‘ON’ position. I began flying.

The gunners had seen us coming. They had seen us coming with our spotlights on for over two miles away. Now they had opened up and their tracers began swirling towards us; some were even bouncing off the smooth surface of the lake. This was a horrible moment; we were being dragged along at four miles a minute, almost against our will, towards the thing we were going to destroy.

I think at that moment the boys did not want to go. I know I did not want to go. I thought to myself: ‘In another minute we will all be dead – so what?’ I thought again, ‘This is terrible – this feeling of fear – if it is fear.’ By now we were a few hundred yards away and I said quickly to Pulford, under my breath: “Better leave the throttles open now and standby to pull me out of the seat if I get hit.” As I glanced at him, I thought he looked a little glum on hearing this.

The Lancaster was really moving and I began looking through the special sight on my windscreen. Spam had his eyes glued to the bomb sight in front, his hand on his button; a special mechanism on board had already begun to work so that the mine would drop (we hoped) in the right spot. Terry was still checking the height. Joe and Trev began to raise their guns. The flak could see us quite clearly now. It was not exactly inferno. I have been through far worse flak fire than that; but we were very low.

There was something sinister and slightly unnerving about the whole operation. My aircraft was so small and the dam was so large; it was so thick and solid and now it was angry. We skimmed along the surface of the lake and as we went, my gunner was firing into the defences and the defences were firing back with vigour, their shells whistling past us, but for some reason, we were not being hit.

Spam said: “Left – little more left – steady – steady – steady – coming up.” The next few seconds seemed a series of kaleidoscopic incidents. The chatter from Joe’s front guns pushing out tracers which bounded off the left-hand flak tower. Pulford crouching beside me. The smell of burnt cordite. The cold sweat underneath my oxygen mask. The tracers whisking past the windows – they all seemed the same colour now – the inaccuracy of those gun positions near the power station; they were firing in the wrong direction.

The closeness of the dam wall. Spam’s exultant, “Mine gone.” Hutch’s red Verey lights to blind the flak gunners. The speed of the whole thing. Someone saying over the R.T., “Good show, leader. Nice work.”

Then it was all over and at last we were out of range and there came over us all, I think, an immense feeling of relief and confidence.

WE WAITED…

As we circled round, we could see a great thousand feet column of whiteness still hanging in the air where our mine had exploded. We could see with satisfaction that Spam had been good, and it had gone off in the right position. Then, as we came closer, we could see that the explosion of the mine had caused a great disturbance upon the surface of the lake and the water had become broken and furious, as though it were being lashed by a gale. At first we thought that the dam itself had broken, because great sheets of water were slopping over the tops of the wall like a gigantic basin. This caused some delay, because our mines could only be dropped in calm water, and we would have to wait until all became still again.

We waited. We waited about 10 minutes, but it seemed hours to us – but it must have seemed longer than that to Hoppy, who was the next to attack. Meanwhile, all the fighters had now collected over our target, they knew our game by now; but we were flying too low for them, they could not see us and there were no attacks. At last – “Hello, ‘M Mother’. You may attack now. Good luck.”

“OK. Attacking.” Hoppy, the Englishman, casual, but very efficient, keen now on only one thing, which was war. He

began his attack.

He began going down over the trees where I had come from a few moments before. We could see his spotlights quite clearly, slowly closing together as he ran across the water. We saw him approach. The flak, by now, had got an idea from which direction the attack was coming and they let him have it. When he was about 100 yards away, someone said, hoarsely, over the R.T. – “Hell, he has been hit.”

‘M Mother’ was on fire; a lucky shot had got him in one of the inboard petrol tanks and a long jet of flame was beginning to stream out. I saw him drop his mine, but his bomb aimer must have been wounded because it fell straight onto the power house on the other side of the dam. But Hoppy staggered on, trying to gain altitude so that his crew could bale out. When he had got up to about 500 feet, there was a livid flash in the sky and one wing fell off; his aircraft disintegrated and fell to the ground in cascading flaming fragments. There it began to burn quite gently and rather sinisterly in a field some three miles beyond the dam.

Someone said: “Poor old Hoppy.”

A furious rage surged up inside my own crew and Trevor said: “Let’s go in and murder those gunners for this.” As he spoke, Hoppy’s mine went up. It went up behind the power house with a tremendous yellow explosion and left in the air a great ball of black smoke; again there was a long wait while we watched for this to clear. There was so little wind that it took a long time.

Many minutes later, I told Mickey to attack. He seemed quite confident and we ran in beside him and a little in front; as we turned Trevor did his best to get those gunners as he had promised.

Bob Hay, Mickey’s bomb aimer, did a good job, and his mine dropped in exactly the right place. There was again a gigantic explosion as the whole surface of the lake shook, then spewed forth its cascade of white water. Mickey was all right; he got through. But he had been hit several times and one wing tank lost all its petrol. I could see the vicious tracer from his rear gunner giving one gun position a hail of bullets as he swept over. Then he called up: “OK. Attack completed.”

It was then that I thought that the dam wall had moved. Of course, we could not see anything, but if Jeff’s theory had been correct, then it should have cracked by now; and if only we could go on pushing it by dropping more successful mines, then in the end it would move back on its axis and collapse.

Once again we watched for the water to calm down – then in came Melvyn Young in ‘D Dog’. I yelled to him: “Be careful of the flak. It’s pretty hot.”

I yelled again: “Trevor’s going to beat them up on the other side. He’ll take most of it off you.”

Melvyn’s voice again: “OK. Thanks.” And so, as ‘D Dog’ ran in, we stayed at a fairly safe distance on the other side, firing with all guns at the defences; and the defences, like the stooges they were, firing back at us. We were both out of range of each other, but the ruse seemed to work and we flicked on our identification lights to let them see us even more clearly.

Melvyn’s mine went in, again in exactly the right spot, and this time a colossal wall of water swept right over the dam and kept on going. Melvyn said: “I think I’ve done it. I’ve broken it.” But we were in a better position to see than he, and it had not rolled down yet. We were all getting pretty excited by now and I screamed like a schoolboy over the R.T. – “Wizard show, Melvyn. I think it’ll go on the next one.”

BREACHED AT LAST

When at last the water had all died down, I called up No.5 – David Maltby – and told him to attack. He came in fast and I saw his mine fall within feet of the right spot; once again the flak, the explosion and the wall of water. But this time we were on the wrong side of the wall and we could not see what had happened. We watched for about five minutes and it was rather hard to see anything, for by now, the air was full of spray from these explosions, which had settled like mist on our windscreens.

Time was getting short so I called up Dave Shannon and told him to come in, but as he turned I got close to the dam wall and then saw what had happened. It had rolled over, but I could not believe my eyes. I heard someone shout: “I think she has gone, I think she has gone.” And other voices took up the call and quickly I said: “Standby until I make a recce.” I remembered that Dave was going in to attack and told him to turn away, and not to approach his target. We had a close look. Now there was no doubt about it; there was a great breach 100 yards across and the water, looking like stirred porridge in the moonlight, was gushing out and rolling into the Ruhr Valley towards the industrial centres of Germany’s Third Reich.

Nearly all the flak had now stopped and the other boys came down from the hills to have a closer look to see what had been done. There was no doubt about it at all – the Möhne Dam had been breached and the gunners on top of the dam, except for one brave man, had all run for their lives towards the safety of the solid ground; this remaining gunner was an extremely brave man, but one of the boys quickly extinguished his flak with a burst of well-aimed tracer.

Now it was all quiet, except for the roar of the water, which steamed and hissed its way from its 150-foot head. Then we began to shout and scream and act like madmen over the R.T., for this was a tremendous sight, a sight which probably no man will ever see again.

Quickly I told Hutch to tap out the message ‘Nigger’ to my station, and when this was handed to the Air Officer Commanding, there was great excitement in the Operations room.

Then I looked again at the dam and at the water, while all around me the boys were doing the same. It was the most amazing sight in the world; the whole valley was beginning to fill with fog from the steam of the gushing water, and down in the foggy valley we saw cars speeding along the roads in front of this great wave of water which was chasing them and going faster than they could ever hope to go.

The floods raced on, carrying with them, as they went, viaducts, railways, bridges and everything that stood in their path; but three miles beyond the dam the remains of Hoppy’s aircraft was still burning gently, a dull red glow on the ground, and I felt solemn and then pleased. Hoppy had been avenged. Then I felt a little remote and unreal sitting up there in the warm cockpit of my Lancaster, watching this mighty power which we had unleashed; and then I felt glad because I knew that this was the heart of Germany, and the heart of her industries, the place which itself had unleashed so much misery upon the whole world.

I circled round there for about three minutes and then I called up all aircraft and told Mickey and David Maltby to go home and the rest to follow me to Eder, where we would try and repeat the performance.

TARGET Y

We set our course from the southern tip of the Möhne Lake, which was already fast emptying itself – we could see that even now – we flew on in the clear light of the early morning towards the south-east. We flew on over little towns tucked away in the valleys underneath the Ruhr Mountains. Little places, these, the Exeters and Baths of Germany; they seemed quiet and undisturbed and very picturesque as they lay sleeping there on the morning of 17 May.

After flying low across the tree tops, up and down the valleys, we at last reached the Eder Lake, and by flying down it for some five minutes, we arrived over the Eder Dam. It took some finding because fog was already beginning to form in the valleys, and it was pretty hard to tell one part of the reservoir filled with water from another valley filled with fog. We circled up for a few minutes waiting for Henry, Dave and Les to catch up; we had lost them on the way. Then I called up on the R.T.

“Hello, Cooler aircraft – can you see the target?”

Dave answered faintly: “I think I’m in the vicinity. I can’t see anything. I cannot find the dam.”

“Standby – I will fire a red Verey light – right over the dam.” No sooner had Hutch fired his Verey pistol than Dave called up again. “OK – I was a bit south. I’m coming up.”

The other boys had seen the signal too, and after a few minutes, we rendezvoused in a left-hand orbit over the target. But the time was getting short now; the glow in the north had begun to get brighter, heralding the coming dawn. Soon it would be daylight and we did not want this in our ill-armed and unarmoured Lancasters.

I said: “OK Dave. You begin your attack.”

Dave circled wide and then turned to go in. He dived down rather too steeply and sparks came from his engine as he had to pull out at full boost to avoid hitting the mountain on the north side.

“Sorry, leader. I made a mess of that. I’ll try again.”

He tried again. He tried five times, but each time he was not satisfied and would not allow his bomb aimer to drop his mine. He spoke again on the R.T. “I think I had better circle round a bit and try and get used to this place.”

“OK Dave. You hang around for a bit and I’ll get another aircraft to have a crack – Hello ‘Z Zebra’ (this was Henry). You can go in now.”

Henry made two attempts. He said he found it very difficult and gave the other boys some advice on the best way to go about it. Then he called up and told us that he was going in to make his final run. We could see him running in. Suddenly he pulled away; something seemed to be wrong, but he turned quickly, climbed up over the mountain and put his nose right down, literally flinging his machine into the valley.

This time he was running straight and true for the middle of the wall. We saw his spotlights together so he must have been at 60 feet. We saw the red ball of his Verey light shooting out behind his tail and we knew he had dropped his weapon.

A split second later, we saw something else; Henry Maudslay had dropped his mine too late. It had hit the top of the parapet and had exploded immediately on impact with a slow, yellow, vivid flame which lit up the whole valley like daylight for just a few seconds. We could see him quite clearly banking steeply a few feet above it. Perhaps the blast was doing that. It all seemed so sudden and vicious and the flame seemed so very cruel. Someone said: “He has blown himself up.”

Trevor – “Bomb aimer must have been wounded.”

It looked as though Henry had been unlucky enough to do the thing we all might have done.

I spoke to him quickly: “Henry – Henry. ‘Z Zebra’ – ‘Z Zebra’. Are you OK?” No answer. I called again. Then we all thought we heard a very faint, tired voice say: “I think so – standby.” He seemed as though he was dazed and his voice did not sound natural. But Henry had disappeared. There was no burning wreckage on the ground; there was no aircraft on fire in the air. There was nothing. Henry had disappeared. He never came back.

Once more the smoke from his explosion filled the valley and we all had to wait for a few minutes. The glow in the north was much brighter and we would have to hurry up if we wanted to get back. We waited patiently for it to clear away.

At last to Dave – “OK. Attack now David. Good luck.”

Dave went in and after a good dummy run, managed to put his mine up against the wall, more or less in the middle. He turned on his landing light as he pulled away and we saw the spot of light climbing steeply over the mountain as he jerked his great Lancaster almost vertically over the top. Behind me, there was that explosion which by now, we had got used to, but the wall of the Eder Dam did not move.

Meanwhile, Les Night had been circling very patiently, not saying a word. I told him to get ready, and when the water had calmed down he began his attack. Les, the Australian, had some difficulty too, and after a while, Dave began to give him some advice on how to do it. We all joined in on the R.T. and there was a continuous amount of backchat going on.

“Come on Les. Come in down the moon, dive towards the point and then turn left.”

“OK Digger. It’s pretty difficult.”

“Not that way, Dig. This way.”

“Too right it’s difficult. I’m climbing up to have another crack.”

After a while I called up rather impatiently and told them that a joke was a joke and that we would have to be getting back. And Les dived in to make his final attack. His was the last weapon left in the squadron. If he did not succeed in breaching the Eder now, then it would never be breached; at least, not tonight.

I saw him run in. I crossed my fingers. But Les was a good pilot and he made as perfect a run as ever seen that night. We were flying above him, and about 400 yards to the right, and we saw his mine hit the water. We saw where it sunk. We saw the tremendous earthquake which shook the base of the dam, and then, as if a gigantic hand had punched a hole through cardboard, the whole thing collapsed. A great mass of water began running down the valley into Kassel.

Les was very excited. He kept his radio transmitter on by mistake for quite some time. His crew’s remarks were something to be heard, but they could not be put into print here. Dave was very excited and said: “Good show, Dig.” I called them up and told them to go home immediately. I would meet them in the Mess afterwards for the biggest party of all time.

The valley below the Eder was steeper than the Ruhr and we followed the water down for some way. We watched it swirling and slopping in a 30-foot wall as it tore round the steep bends of the countryside. We saw it crash down in six great waves, swiping off power stations and roads as it went. We saw it extinguish all the lights in the neighbourhood as though a great black shadow had been drawn across the earth. It all reminded us of a vast moving train. But we knew that a few miles further on lay some of the Luftwaffe’s largest training bases. We knew that it was a modern field with every convenience, including underground hangars and underground sleeping quarters… We turned for home.

THE RUN HOME

Dave and Les, still jabbering at each other on R.T., had, by now, turned for home as well. Their voices died away in the distance as we set our course for the Möhne Lake to see how far it was empty. Hutch sent out a signal to base using the code word, ‘Dinghy’, telling them the good news – and they asked us if we had any more aircraft available to prang the third target. “No, none.” I said. “None,” tapped Hutch.

Now we were out of R.T. range of our base and were relying on W.T. for communication. Gradually, by code words, we were told of the movements of the other aircraft. Peter Townsend and Anderson of the rear formation had been sent out to make lone attacks against the Sorpe. We heard Peter say that he had been successful, but heard nothing from Anderson.

“Let’s tell base we’re coming home and tell them to lay on a party.” Suggested Spam. We told them we were coming home.

We had reached the Möhne by now and circled twice. We looked at the level of the lake. Already, bridges were beginning to stick up out of the lowering water. Already, mudbanks with pleasure boats sitting on their sides could be seen. And below the dam, the torpedo nets had been washed to one side of the valley, the power station had disappeared. The map had completely changed as a new silver lake had formed, a lake of no strict dimensions; a lake slowly moving down towards the west.

Base would probably be panicking a bit, so Hutch sent out another message telling them that there was no doubt about it. Then we took one final look at what we had done and afterwards turned north to the Zuider Zee.

We flew north in the silence of the morning, hugging the ground and wanting to get home. It was getting quite light now and we could see things that we could not see on the way in – cattle in the fields, chickens getting airborne as we rushed over them, and farm life. On the left, someone flew over Hamm at 500 feet. He got the chop. No one knew who it was. Spam said he thought it was a German night-fighter which had been chasing us.

I suppose they were all after us. I suppose that now that we were being plotted on our retreat to the coast, the enemy fighter controllers would be working overtime. I could imagine the Fuehrer himself giving his orders to “stop those air pirates at all costs.” After all, we had done something which no one else had ever done and Hitler would not like it. Water when released can be one of the most powerful things in the world – similar to an earthquake – and the Ruhr Valley had never had an earthquake.

Terry looked up from his chart board. “About an hour to the coast,” he said. “Oh hell.” I turned to Pulford. “Put her into maximum cruising. Don’t worry about petrol consumption.” Then to Terry – “I think we had better go the shortest way home crossing the coast at Egmond – you know the gap there. We’re the last one and they’ll probably try to get us if we lag behind.”

Terry smiled and watched the air-speed needle creep round. We were now doing a smooth 240 indicated and the exhaust stubs glowed red hot with the power she was throwing out. Trevor’s warning light came on the panel, then his voice – “Unidentified enemy aircraft behind.”

“OK. I’ll sink to the west – it’s dark there.”

As we turned – “OK. You’ve lost it.”

“Right. On course. Terry, we’d better fly really low.”

These fighters meant business but they were hampered by the conditions of light during the early morning. We could see them before they saw us – which was good.

Down went the Lanc until we were a few feet off the ground, for this was the only way to survive. And we wanted to survive. Two hours before we had wanted to burst dams. Now we wanted to get home – quickly. Then we could have a party. Minutes passed…

Terry spoke: “Thirty minutes to the coast.”

“OK. More revs.”

The needle crept round. It got very noisy inside.

We were flying home – we knew that. We did not know whether we were safe. We did not know how the other boys had got on. Bill, Hoppy, Henry, Barlow, Byers and Ottley had all gone. They had all got the hammer. The light flak had given it to most of them, as it always will to low-flying aircraft, that is, the unlucky ones. They had all gone quickly, except, perhaps, for Henry. Henry, the born leader, his was a great loss but he gave his life for a cause for which men should be proud. Boys like him are the cream of our youth. They die bravely and they die young.

I called up Melvyn on the R.T. He had been with me all the way round as deputy leader when Mickey had gone home with his leaking petrol tank. He was quite all right at the Eder. Now there was no reply. We wondered what had happened.

Terry said: “Fifteen minutes to go.”

Fifteen minutes. Quite a way yet – about 100 miles. A long way and we might not make it. We were in the black territory. They had closed the gates of their fortress and we were locked inside, but we knew the gap – the gap by those wireless masts at Egmond. If we could find that, then we would get through safely.

We did not know anything about the fuss, the press, the publicity which would go around the world after this effort. Or the honours given to the squadron, or of trips to America and Canada, or of visits by important people. We did not care for any of these things. We only wanted to get home. We knew that the boys had done a good job, but this was the success of an ambition, the success of an achievement made possible by the work of ordinary boys flying ordinary aeroplanes, but boys who had guts. And what boys!

We did not know that we had started something new in the history of aviation, that our squadron was to become a by-word throughout the RAF as a precision bombing unit – a unit which could pick off anything from viaducts to gun emplacements, from low level or high level, by day or by night. A squadron consisting of crack crews using all the latest new equipment and the largest bombs, even earthquake bombs. A squadron flying new aeroplanes and flying them as well as any in the world.

Terry interrupted. “Rotterdam’s 20 miles on the port bow. We will be getting to the gap in five minutes.” Now they could see where we were going, the fighters would be streaking across Holland to close that gap, then they could hack us down.

I called up Melvyn but he never answered. I was not to know that Melvyn had crashed into the sea a few miles in front of me. He had come all the way from California to fight this war and had survived 60 trips at home and in the Middle East, including a double ditching. Now he had ditched for the last time. Melvyn had been responsible for a good deal of the training that made this raid possible. He had endeared himself to the boys and now he had one.

And so, out of the 16 aircraft which had crossed the coast to carry out this mission, eight had been shot down, including both Flight Commanders.

“North Sea ahead, boys,” said Spam.

And there it was. Beyond the gap in the distance lay the calm and silvery sea, and freedom. It looked beautiful to us then – perhaps the most wonderful thing in the world. Its sudden appearance in the grey dawn came to us like the opening bars of the Warsaw Concerto – hard to grasp, but tangible and clear.

We climbed up a little to about 300 feet. Then – “Full revs and boost, Pulford.” As he opened her right up, I shoved the nose down to get up extra speed and we sat down on the deck at about 260 indicated.

Woodhall Spa. Jarrod Cotter

“Keep to the left of this little lake,” said Terry, map in hand. This was flying. “Now over this railway bridge.” More speed.

“Along this canal…” We flew along that canal as low as we had flown that day. Our belly nearly scraped the water, our wings would have knocked horses off the towpath.

“See those radio masts?”

“Yeah.”

“About 200 yards to the right.”

“OK.”

The sea came closer. It came closer quickly as we tore towards it. There was a sudden tenseness on board.

“Keep going, you’re OK now.”

“Right. Standby front gunner.”

“Guns ready.”

Then we came to the Western Wall. We whistled over the anti-tank ditches and beach obstacles. We saw the yellow sand dunes slide below us silently, yellow in the pale morning.

And then we were over the sea with the rollers breaking on the beaches and the moon just sitting in the west casting its long reflection straight in front of us – and England.

We were free. We had got through the gap. It was a wonderful feeling of relief and safety. Now for the party.

“Nice work,” said Trevor from the back.

“Course home?” I asked.

Behind us lay the Dutch Coast, squat, desolate and bleak, still squirting flak in many directions. We would be coming back.

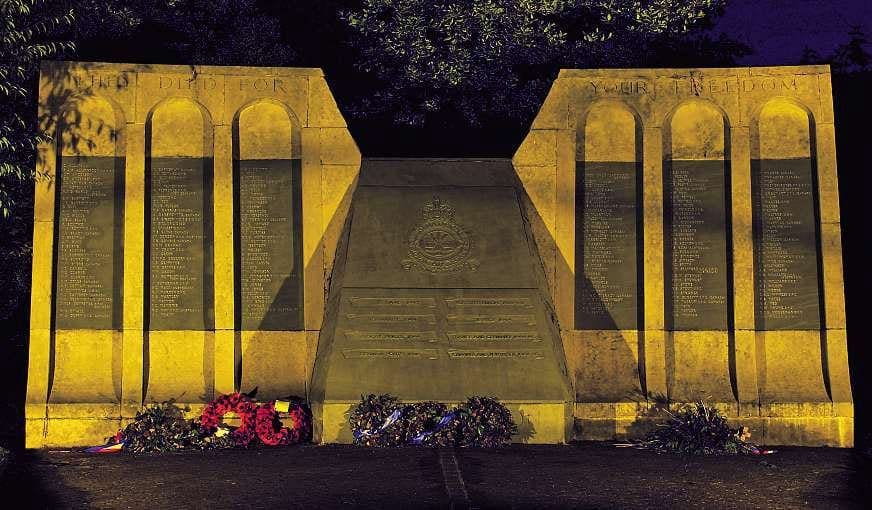

617 SQUADRON MEMORIAL

Woodhall Spa is situated in the heart of Lincolnshire, often referred to as ‘Bomber County’, which has numerous aviation memorial sites. One of the most impressive is that of 617 Squadron, which operated out of RAF Woodhall Spa from January 1944 to May 1945. During the war, the Petwood Hotel in Woodhall was requisitioned by the Air Ministry to serve as the base’s Officer’s Mess.

The squadron’s memorial was built in 1987, and the large structure takes on the form of the breached Möhne Dam. At the top are the words: ‘They died for your freedom’, with the names of ‘Dam Busters’ personnel who were killed listed on the sidewalls. Centrally there is a representation of water pouring through the breach, and on that is engraved the squadron’s badge and Battle Honours. The monument stands in Royal Square, formally the site of the Royal Hydro Hotel and Winter Gardens, which were destroyed by a bomb in 1943.

ENEMY COAST AHEAD

First published in 1946, the beautifully written book Enemy Coast Ahead quickly became regarded as a classic insight into wartime life within the RAF. Guy Gibson wrote it in 1944 – the same year in which he was later killed on operations. It describes his exploits from flying the Handley Page Hampden at the beginning of the war to the formation of ‘Squadron X’ (as it was termed before being designated 617 Squadron) and the Dams raid for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross. The book can be thoroughly recommended and is currently published in its complete and uncensored form by Crécy Publishing Ltd.www.crecy.co.uk