How do you tell the story of a legend, a national icon and one of the most amazing flying machines ever built in a single page? Well, it’s difficult. Like the Mosquito issue, this introduction has seen a few drafts to get to this stage.

How do you tell the story of a legend, a national icon and one of the most amazing flying machines ever built in a single page? Well, it’s difficult. Like the Mosquito issue, this introduction has seen a few drafts to get to this stage.

To understand the Hurricane, you have to understand the urgency that created it. When the British Government finally admitted that another war in Europe was inevitable, the front line RAF fighters were open cockpit biplanes. Can you imagine the likely outcome of Bf 109Ds against Demons, Furys and Gauntlets? It would have been like fish in a barrel. So a huge expansion and rearmament programme began, to swell the ranks of the armed forces not just in size, but in capability, through more modern equipment.

Two designs were chosen as the new single seat fighters for the RAF. These were the Supermarine Spitfire, which became the most famous British fighter of the Second World War, and the Hawker Hurricane.

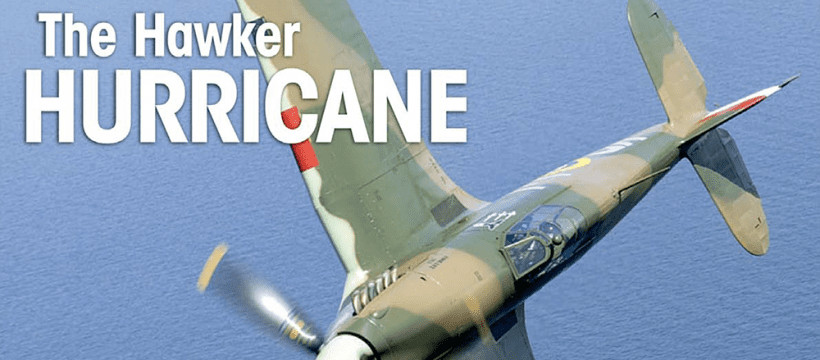

The Hawker Hurricane was an amazing aircraft. It was cheap, easy to build and incredibly tough. It was built using the same methods as earlier biplane designs and had originally been known as the ‘Monoplane Fury’. The frame of the aircraft constituted metal tubes and die stamped sheet metal parts, riveted and bolted together instead of welded, then covered in a predominantly fabric skin.

Hawker’s chief designer, Sydney Camm, had broken the design down into simple tasks, which meant his factory workers, already familiar with the techniques, knew how to build the new fighter and could build it quickly. Given the simple nature of the sub-assemblies, new staff could be easily trained to expand production rapidly if needed. This was most important, as Britain would soon need as many modern fighters as possible.

The first Hurricane flew on November 6, 1935, its performance ensured the Government ordered 600 in 1936.

Over the next 10 years, 136 squadrons of the RAF, 16 of the Royal Navy and 48 other units were to be equipped with Hurricanes. Its inherent strength and ease of use endeared it to everyone associated with it. The type was easily mastered by neophyte pilots and was deadly in the hands of experienced men. It saw action in every theatre of the war and was pitched against the Axis at a time when the opposition was in the ascendancy. Hurricanes held the line in the Mediterranean, the Far East and at sea for two years, because at the time it was all Britain had. By the time Spitfires and other types were available to enter a theatre in numbers, the Hurricane had already fought the enemy to a standstill. Time and again this happened, over Malta, in Egypt, in Burma, the Hurricane Squadrons dug in, held on and fought for their lives with little hope of relief.

It is often quoted that, during the Battle of Britain in 1940, Hurricane squadrons destroyed more enemy aircraft than all the other forms of defence put together. While this is true, what is a greater tribute is that the fighter accounted for just over 50% of all enemy aircraft shot down by British and Commonwealth forces throughout the entire war. This is amazing when one considers that the Hurricane had, by 1942, been relegated from front line fighter to ground attack aircraft.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Second World War may have had a very different outcome had the RAF not had such a robust aircraft available in such numbers.

When compared with other fighters of its era, the Hurricane’s conservative construction severely limited its potential for development. After the battles of 1940, both the Spitfire and the Bf 109 were progressively and extensively developed, while the Hurricane was only modestly improved. The final versions of the Spitfire hardly resemble the dainty fighter of 1937, but the Hurricane’s appearance changed very little, retaining its hunchbacked, porpoise look, always appearing far more pugnacious a fighter than some other types.

Its ability to operate reliably from poorly equipped rough air strips in the desert and jungle, or from the pitching deck of a small ‘Woolworth’ aircraft carrier is an everlasting testimony to the robustness of the design.

Although some people have said that the Hurricane was obsolete at the beginning of the Second World War, it was to see service right up to the war’s end, the airframe’s versatility kept it at the forefront of the fighting overseas. Perhaps the best tribute to the Hurricane’s toughness came from German fighter pilot and eventual General of Fighters Adolph Galland, who commented that you could shoot all your ammunition into a Hurricane and have big pieces fly off, but it would keep flying and fighting. Therefore it must have been made of lots of spare parts!

This issue of Aviation Classics is intended as a tribute to the men and women who designed and built the fighter, flew it into battle, and maintained it in difficult circumstances in every theatre of the Second World War. It is also a tribute to the 14,533 Hurricanes themselves, the tough little fighters that did many jobs, and kept flying and fighting when other aircraft could not.

This issue of Aviation Classics is intended as a tribute to the men and women who designed and built the fighter, flew it into battle, and maintained it in difficult circumstances in every theatre of the Second World War. It is also a tribute to the 14,533 Hurricanes themselves, the tough little fighters that did many jobs, and kept flying and fighting when other aircraft could not.

All best,

Tim

Contents

Contents

8 Determination, courage and genius

20 Prototype, testing and production

24 Into service

28 Over France in 1940

34 The Battle of Britain: Phase 1 and 2

40 The Battle of Britain: Phase 3 and 4

44 Hurricane Squadrons of the Battle of Britain

46 Storm at sea

52 Refining the breed

58 Night Hawks

70 A Greek in the RAF – Eagle Squadron

78 Comrades in arms

82 Inside the Hurricane

92 Flyinglass competition

94 Displaying a legend

102 Hurricanes in the Mediterranean

108 Versatility in action

114 Hurricanes abroad

124 Survivors

Refining the breed – The Mk.II, IV and V

Service experience with the Hurricane Mk.I highlighted two operational requirements which would need to be addressed if the fighter was to continue in front line service. The first was for more firepower, the second for greater speed. Hawker began addressing these requirements as early as 1939, developing re-engined and re-armed variants that began entering service towards the end of the Battle of Britain. The increased firepower helped the Hurricane to fill new roles, and was to keep the aircraft on the front line until the end of the Second World War.

Service experience with the Hurricane Mk.I highlighted two operational requirements which would need to be addressed if the fighter was to continue in front line service. The first was for more firepower, the second for greater speed. Hawker began addressing these requirements as early as 1939, developing re-engined and re-armed variants that began entering service towards the end of the Battle of Britain. The increased firepower helped the Hurricane to fill new roles, and was to keep the aircraft on the front line until the end of the Second World War.

It was quickly realised that the need to improve the Hurricane’s performance could not be met with the existing Merlin III engine. Two aircraft, L1856 and L2026, were therefore used for trials with two different versions of the Merlin during 1939, but it was not until mid-1940 that the fully developed Merlin XX was available.

The new engine initially produced 1185hp and very few changes were required to fit this to the Hurricane I airframe, designed as it was for maximum compatibility with earlier variants. The basic structure of the early Mk.II was virtually identical to the Mk.I; however, the opportunity was taken for detail design changes to solve issues revealed by service use. The machines that appeared from October 1940 onwards, known at this stage as Series 2, introduced a slightly longer, re-profiled nose and a semi circular oil splash guard behind the propeller.

On June 11, 1940, Hawker test pilot Philip Lucas took Hurricane P3269 on its first flight from the company’s Langley airfield with the new engine installed. A Rotol constant speed propeller was fitted and the aircraft was fully armed with eight machine guns. The overall weight was just less than 6700lb (3040kg) and this machine was the fastest armed Hurricane ever built, capable of 348mph (560kmh) in level flight.

Hurricanes with the new engine were designated as Mk.IIs from December 1940, but production had begun in August 1940. A few were issued to front line squadrons, including 111, during the Battle of Britain. The increase in available power raised the Hurricane’s top speed to a more respectable 342mph (550kmh); however, this was still some 15 to 20mph (24 to 32kmh) slower than the contemporary Spitfire I and Bf 109E.

A strange phenomenon was encountered with the Mk.II at this stage. It became uncontrollable at altitudes previously unobtainable by earlier versions of the Hurricane. The cause was found to be the lubricating grease used in the controls. This was unsuitable for high altitudes and froze, locking the flying surfaces. Early Mk.IIs were armed with eight .303 Browning machine guns and designated Mk.IIAs. The Mk.I remained in squadron service well into 1941, but was gradually replaced as the new aircraft rolled off the production lines. Many Mk.Is found their way into training units, where even a few very early machines with fabric covered wings continued to give good service.

Increasing the firepower

As early as 1939, consideration had been given to improving the firepower of British fighters. The eight Browning machine guns had a high rate and density of fire, but it was apparent that the rifle calibre bullets were becoming increasingly ineffective. As an interim measure, the number of machine guns was increased to 12 by fitting two additional pairs of .303 Brownings towards the wing tips, outboard of the wing leading edge landing lights.

To accommodate these guns it was necessary to mount them further forward than the main battery, so the muzzles projected beyond the wing’s leading edge. The inner gun of each extra pair was mounted slightly higher than the other guns and was fed from a magazine inboard of it. The outboard guns were fed from the opposite side. The Hurricane’s wing was so thick and spacious, even at this distance from the root, no blisters or other contour changes were necessary. Hurricanes so armed were referred to as Mk.IIBs.

Aircraft cannons had been investigated as early as the mid 1930s. Despite having a lower rate of fire than a machine gun, cannons were able to fire a wider variety of explosive and armour piercing ammunition. Several old airframes were tested on ranges and the effects of cannon fire were impressive, as it took only a few hits to cause lethal damage. The Air Ministry was in the process of negotiating manufacturing licenses from Hispano and Oerlikon for their 20mm cannons, but at this stage it was thought they would be too heavy for use in single engined fighters.

As a trial of the Swiss Oerlikons, two were fitted to Hurricane L1750 in 1939, carried below the wings. This installation was less than satisfactory and the aircraft was not used operationally. The French Hispano cannon was considered most suitable for the next generation of British fighters so arrangements were made for the parent company to establish a factory in Grantham, under the convoluted title the British Manufacturing and Research Company.

Several pairs of unserviceable wings were returned to Hawker to experiment with the installation of four Oerlikon cannon into the existing gun bays. The breeches could be accommodated in the vast bays, but the barrels projected well ahead of the wing. Small aerodynamic blisters on the gun access panels were necessary to clear the breech of each gun. Hurricane Mk.I V7360 was fitted with cannon wings and flew the full installation, but with drum fed guns, for the first time on June 7, 1940.

The first production version of the Mk.IIC, V2461, had belt fed guns. The additional weight of the guns and ammunition reduced the aircraft’s speed considerably and it was unable to achieve even 300mph (482.8kmh). The potential to create a heavily armed fighter was recognised, but the limiting factor at the time was the relatively low power of the Merlin III engine.

During the Battle of Britain, V7360 was delivered to 46 Squadron at North Weald, still fitted with four cannons and used during the intense fighting in September. The gun feeds often failed to function correctly or jammed but at least one German bomber was claimed by Flight Lieutenant Alexander Rabagliati. The problems with the feed mechanism were overcome by the new Chatellerault feed, and with the introduction of more powerful versions of the Merlin, paved the way for full scale production of the cannon armed Hurricane Mk.IIC, which first flew on February 6, 1941. This mark would become the most widely used version of the Hurricane, with over 4700 built, mostly by Hawker at Langley. The wing was largely unchanged, except for the gun bays, which now had additional access panels on the undersurface to allow access to the cannon cocking levers and spent ammunition chutes. The cannons exerted a much greater recoil force than the machine guns which were dampened by prominent recoil springs around each barrel. Hurricane Mk.IICs entered RAF service in May 1941 and were among the world’s most powerfully armed fighters at the time.

Hurribombers

The wing of the Hurricane Mk.II could also accept external stores. Either two 44 gallon (200 litre) external fuel tanks or a pair of 250lb (113.4kg) bombs could be carried, one under each wing. When bombs were carried it was usual practice to reduce the number of machine guns by two, the Brownings directly above the pylon attachment point being removed for better access.

The range of the ‘Hurribomber’, as they were unofficially known, was not greatly affected by the extra weight, but the aircraft’s speed was considerably reduced. The first attack took place on October 30, 1941, when a pair of Mk.IIBs attacked an electrical distribution installation near Tingery. At about this time other modifications to the Hurricane were considered, a new Spitfire sliding canopy devoid of the heavy metal framework was tested on at least one aircraft and a four bladed Rotol propeller was flow as early as December 1940. Neither modification was adopted as the Hurricane was seen as belonging to a previous generation and Hawker was preparing to produce the Typhoon.

When operations over northern France began, it was quickly found that the Hurricanes could not operate without fighter escort. Even with the greater power of the Merlin XX, Hurricanes were outclassed by new versions of the Luftwaffe’s Bf 109. Even more dramatic was the advantage enjoyed by the superb Focke-Wulf 190A, which outclassed even the latest incarnation of the Spitfire until the introduction of the Mk.IX. In a reversal of the previous year’s fighting, 1941 saw the RAF go on to the offensive, using fighter sweeps often mixed with a few Blenheims or ‘Hurribombers’ to force the Luftwaffe to engage in combat. Spitfires were the obvious choice for the escorts, on occasion outnumbering their charges by as many as three to one in an attempt to draw enemy fighters into combat.

Targets included forward Luftwaffe bases and the railway network, where the destructive power of the four cannon was proved beyond doubt. These operations confirmed the fighter-bomber concept; Hurricanes, once free of their bombs, were restored to being moderately useful fighters, whereas the slower Blenheim was a liability for the escorting fighters both to and from the target. By the latter half of 1941, it was apparent that the Hurricane was drawing to the end of its operational usefulness over Europe by day, despite the fact that more than 50 squadrons were equipped with the type.

German night raids on Britain continued throughout 1941. As a stop gap measure, Hurricanes were used to patrol high value target areas, often working in conjunction with Boulton Paul Defiants. Night fighter and night intruder operations will be covered later in this magazine. Hurricane IICs of 43 Squadron were among the first aircraft involved in the abortive raid on Dieppe on August 19, 1942, known as Operation Jubilee, which ultimately failed to achieve any of its objectives.

The RAF lost 106 aircraft in the action and nearly two thirds of the landing force of 6000 troops were either killed or taken prisoner. Despite this, crucial lessons were learned that would pay great dividends when the Allies returned to mainland Europe in 1944. This was the last occasion that Hurricanes were used in great numbers in an offensive capacity over Europe. The Hurricane Mk.IID was a ground attack aircraft fitted with a pair of podded Vickers 40mm ‘S’ guns for anti-tank missions. These are described later in this magazine.

Rocket projectiles

The next and perhaps the most important development in British aircraft armament was the rocket projectile (RP). Hurricane Mk.IIA Z2415 was selected as the test bed for the new weapon, as it had already been strengthened for previous aerodynamic trials. The aircraft was first flown on February 23, 1943, with six rockets under each wing. It was later passed to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Boscombe Down for further trials and development. The production RP had a 60lb (27.2kg) warhead and four stabilising fins at the rear of the tube containing the propellant.

As the weapon was being developed the number of rockets carried by an individual aircraft was increased to eight. The rocket had many advantages over bombs and cannon. With practice, ground attack pilots could deliver them with great accuracy and they were effective against almost every type of battlefield or surface target. There was no recoil as the rockets left the rails, although pilots experienced a brief period of turbulence as the launch aircraft passed through their wake.

The launch rails were mounted on a thin steel plate to protect the wings from the blast effects as the rockets were launched, in either pairs or in a salvo of all eight. Once the Hurricane had launched its rockets, it reverted to its fighter role and therefore did not require escort in the traditional manner. Rockets were used over mainland Europe for the first time by 137 and 164 Squadrons on September 2, 1943, against the lock gates at the Hansweert Canal in Holland.

This was among the last offensive actions undertaken by Hurricanes in Western Europe, but in the Middle and Far East the RP was to keep the Hurricane at the forefront of the fighting. A single Mk.IV was employed to test the massive Long Tom rocket during 1945. The warhead weighed 500lb (226.8kg) and only two could be carried, but the weapon was never used operationally by RAF Hurricanes.

Hurricane Mk.IV and V

During 1942 the Hurricane was evolving into a specialist ground attack aircraft and as such would need an adaptable wing that could be reconfigured in the field for the varied missions the aircraft was expected to undertake. The universal wing was designed to accept bombs of 250 or 500lb (113.4 or 226.8kg), long range fuel tanks of 45 or 90 gallon (200 or 400 litre) capacity, or the Vickers 40mm cannon in pods. It was also wired to carry rockets and smoke generators to lay smoke screens. Just two Browning machine guns were retained for sighting purposes. This version was initially referred to as the Mk.IIE, but after production commenced a new designation was created.

Externally, the Mk.IV was identical to the standard Hurricane Mk.II, with the exception of the heavily armoured radiator, which now had an angular, flat sided appearance. Many liquid cooled aircraft were lost at low level through damage to the coolant system, so additional armour was fitted around this, the engine and cockpit. The Mk.IV weighed 6150lb (2790kg) empty, in comparison to the Mk.IIA’s 5150lb (2336kg), and was powered by a Merlin 24 or 27 engine producing 1620hp. Hawker test pilot Philip Lucas flew the first Hurricane Mk.IV KX405 on March 14, 1943.

More than 500 Mk.IVs entered service with 20 RAF Squadrons, all of which were built in the UK by Hawker Aircraft and Austin Motors. In service the type upheld the Hurricane’s reputation as a robust and reliable machine. The Mk.IV Hurricanes had serial numbers preceded by the following letters: HL, HM, HV, HW, KW, KX, KZ, LB, LD, LF, PG and PG. In Burma, Mk.IVs were frequently operated with an asymmetric payload of a single fuel tank and four rockets.

In early 1943, two Hurricane Mk.IVs were taken from the production line and converted to accept the Merlin 32 engine which was tailored to low level performance and produced 1700hp. To absorb this power, a Rotol four bladed propeller was installed. The intention was to produce an even more powerful low level attack aircraft coupled to the universal wing of the Mk.IV for use in the Far East. The new version was to be known as the Mark V.

The first, KZ193, was flown by Lucas shortly after he had tested the first MkIV, on April 3, 1943, and was fitted with Vickers ‘S’ guns. The second conversion, KX405, was completed with a bulged engine cowling to fully accommodate the Merlin 32. A single prototype Mk.V, NL255, was built, but no further aircraft were ordered as production of a new version so similar in performance was considered unnecessary. The Mk.V was predictably the heaviest of all the Hurricanes at 6405lb (2905kg) empty. It was almost a third heavier than the Mk.I. Fully laden it had a maximum takeoff weight of 9300lb (4218kg).

As one would expect for such a widely used aircraft, the Hurricane was subject to numerous tests and trials. Alternative power plants were considered such as the Napier Dagger and the Bristol Hercules. At one stage the 2000hp Griffon was considered, but the engineers at Rolls-Royce were able to extract ever more power from the Merlin, making such measures unnecessary.

Other Hurricanes were employed to gather high altitude weather data by the meteorological flights. This lonely and unglamorous role was diligently undertaken by single flights in the UK, Egypt and Iraq. Hurricanes modified for this role had sensors and rudimentary recording equipment mounted on the starboard wing. As a stopgap measure, several Hurricanes were converted to carry out photo reconnaissance (PR) missions.

To meet the urgent need for a suitable high level reconnaissance platform on Malta, Hurricane V7101 was stripped of all non essential items to save weight and improve performance. At some time the empty gun bays were used to house additional fuel tanks probably salvaged from other aircraft on the island so the aircraft could reach Sicily. In the hands of Flight Lieutenant George Burgess it provided valuable intelligence about enemy activity.

Burgess stated that the aircraft displayed some undesirable flying characteristics at very high altitude, probably as a result of the rearward shift of the centre of gravity when two F.24 cameras were installed behind the pilot’s seat.

The Hurricane was replaced by dedicated PR versions of the Spitfire as they became available. At least one Mk.II was also adapted for the role and was fitted with as many as four vertical cameras to give as wide a field of coverage as possible.

A Greek in the RAF Eagle Squadron

A Greek in the RAF Eagle Squadron

As one of the foreign pilots who flew with the RAF before the American squadrons arrived in England, Spiros ‘Steve’ Pisanos of Greece became a double ace and the first American citizen to be naturalised in an overseas ceremony.

As one of the foreign pilots who flew with the RAF before the American squadrons arrived in England, Spiros ‘Steve’ Pisanos of Greece became a double ace and the first American citizen to be naturalised in an overseas ceremony.

Spiros Pisanos was born in Athens, Greece, in 1919 and it wasn’t long before he became completely infatuated with aviation. But his ambition to become a pilot was frustrated at first. He said: “I first fell in love with aeroplanes when I was young, and when I was 12 years old I was planning to attend the Greek Air Force Academy. Unfortunately, I was so bad in school that I did not have the qualifications to take the exams.” It was time for plan B.

“Near the end of high school, I began to dream about going to America to become an aviator,” he said. “My first attempt was to stow away on the Italian liner Rex when it had arrived in Athens to pick up passengers bound for New York, but they found me.”

Time to commence plan C. Steve said: “Later on I was playing football with my friends and a fellow wanted to join. He was an American from Buffalo, New York, visiting his uncle, who was a friend of my father. I told him about what I had attempted to do on the Italian liner.

“He told me that I would have probably died in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, but that there was another way. ‘Get a job on a Greek merchant ship and eventually when that ship arrives in an American port, just jump off, walk away and get yourself to New York. There you will find many Greeks’. So that is exactly what I did. The only places I knew about in America were New York City, Chicago with the gangsters, and the West with the cowboys.”

Pisanos left Greece on March 25, 1938, and jumped ship while docked in Baltimore, Maryland, in the middle of April. He got on to a train bound for New York City.

“I arrived at Pennsylvania Station and when I walked out, honest to God I was crying like a baby that lost its mother at the shopping centre,” he said. “There were Greek and American flags on a small theatre where they were playing the first movie made in Greece, a movie I had seen. Behind me I overheard two gentlemen talking about the movie in Greek.”

Those two brothers he met in front of the theatre brought Pisanos to where they lived in Brooklyn.

“The older brother was a chef, and his friend worked for an employment agency for restaurants and bakeries,” said Steve. “He got me a job at a bakery at 147th St and Broadway that was owned by a Greek family. I went to a recruiting office to join the Army, but they noticed my accent and discovered I wasn’t an American, so they wouldn’t take me.” Trying a different angle now, all of Steve’s spare money went towards taking flying lessons. “There was a flying school at the airfield in Brooklyn, like a flying club. You had to pay 25 dollars… and I started to fly,” he said.

“Unbelievable! Well, I had a friend who told me about how in New Jersey I could pay eight dollars for instruction, and six dollars for solo (Brooklyn was 12 dollars and eight for solo). So, I quit my job and told the employment agency fellow that I needed to move to New Jersey.

“I got a job at the Park Hotel by the Westfield airport, where the cheap flying was. The owner of the hotel was a German guy who had come to America the same way. He had been a waiter on the SS Bremen and when they stopped in New York he said, ‘to hell with this life’.”

Steve impressed the owner to the point that he soon offered to send him to Cornell to learn the hotel business, but Steve wasn’t interested. “I told him the centre of my heart was in the airplanes,” he said. “In late April 1941, the newspaper reported how the Germans were shelling the Greeks in Athens and stealing all the food they could and sending it to Germany. I was really upset and when I got to the airport my instructor spotted me and asked why I looked so angry. I told him what I had seen in the paper and if I could only get my hands on a plane to fight those damned Germans.

“He asked me ‘do you really want to fight the Germans? How would you like to join the RAF? In New York they have a recruiting office at the Waldorf Astoria on the 13th floor, they are looking for aviators. Look for the sign on the door that says The Clayton Knight Committee’.”

It was the HQ for the American Eagle Squadron which had been formed 18 months earlier, with Squadron 71 becoming operational early in 1941, equipped with the Hawker Hurricane. Eventually there were three RAF Eagle Squadrons, the 71, 121 and 133, and by this time some of the earlier issues, such as asking Americans to swear allegiance to the Crown, had been resolved.

Steve said: “My instructor told me to take my licence and logbook, as I had a private licence by that time with 170 hours. I got there and said that I was there to enquire about joining the Royal Air Force, so they introduced me to Squadron Leader George Graves, the man who was in charge of recruiting civilian aviators.

“He informed me that the minimum was 200 hours, and I told him if he would allow me, I’d go back to fly some more and come back later on. Graves said ‘that won’t be necessary’ and he turned to his secretary and asked her to help Mr Pisanos to fill out his application. Then he told me that he would call and let me know.

“I was so happy you have no idea… when I got back to the hotel, I didn’t say anything to anyone. A month later the public phone rang in the dining area and a waiter said ‘Steve, somebody wants you on the phone’. A voice said ‘Mr Pisanos, this is Squadron Leader Graves from New York… you have been accepted to join the Royal Air Force. You need to take a flight check at Flushing Airport and take a physical’. I did the physical and then did my flight check with a Stearman biplane that I had never flown. The old pilot that gave me the check was a First World War fighter pilot. We did some acrobatics, this and that and he didn’t say anything yay or nay.

“After the flight, we sat down for coffee. I was so damn anxious to hear from the guy… and then he said ‘for never having flown that aircraft before, you did very well my boy. You are going to the Polaris flight academy where you’ll get some more training’. I asked the guy behind the counter to give us some apple pie with ice cream, I was so happy! This was in October of 1941.

“Now I was faced with… how do I tell my good German boss Albert Stender, who had helped me so much? I went to his office and told him that I had joined the Royal Air Force and that I was going to England to probably fight the German air force. He got up and came around to where I was sitting and said ‘Steve, I have never approved of what Hitler and all his gang have done to Germany, my country. Germany is in my heart like Greece is in your heart. I want you to go there and give Hitler and his pals hell’.

“He had a big shindig for me with the newspapers about the boy from the Park Hotel who has joined the RAF… it was unbelievable. When I was over in England, you wouldn’t believe all the packages of cookies and things I received from his wife. In November, I reported to the Polaris flight academy.”

Soon it was off to England and flying with the RAF. Steve said: “I was with the 268 Squadron, flying the Hurricane, P-40s, and P-51s with the Allison engine, not the later model with the Rolls-Royce engine. Well, one day I got a phone call from a wing commander of the Greek Air Force and he told me that he wanted me to come to London and that he needed to talk to me.

“I told my flight commander, who said ‘you’d better go then’. This Wing Commander Kinatos was the aide to King George, who was also staying at this hotel since he escaped from Greece when the Germans invaded. The wing commander told me how many of the Greek Air Force pilots had escaped to Egypt, Malta, and Cyprus.

“To find his pilots he had sent his people to the Air Ministry for a list of every pilot in the RAF, to pick out the Greek names. I told him that I belonged to an RAF squadron here and that if I survived the war, I wanted to go back to America. He was getting kind of angry, telling me that I was a Greek soldier and that I had to go to Egypt… when I had nothing to do with the Greek Air Force.

“I walked out and figured I’d better go to the Eagle Club where the manager was Mrs Dexter, an American lady who had gone to England. I told her that I needed to talk to Squadron Leader Chesley Peterson, the commander of the 71st Eagle Squadron, who I’d met before. She got him on the phone, and I told him that I needed to speak with him about something important.

“So, I met him at the Regent Palace Hotel by Picadilly Square. He asked me ‘do you want to go to Egypt?’ and I said ‘no sir, I want to stay here in the RAF’. So he told me that he was going to Fighter Command tomorrow, and to let him handle this. The following day, Wing Commander Anderson of 268 Squadron said ‘what is this? I just got a phone call from Fighter Command telling me to release you immediately to report to 71 Eagle Squadron’.

“I got into the 71st Eagle Squadron of the RAF, flying Spitfires V’s in the very beginning of September 1942. Don Gentile was my room mate during the rest of the war, and he ended up with 28 aircraft destroyed – 22 in the air and six on the ground.

“But it was mostly a ‘rhubarb mission’, what in RAF terminology meant strafing locomotives. That and convoy patrol. I destroyed a couple of locomotives in France. When the American Eighth Air Force came over to England, they didn’t have any experienced fighter pilots then. Guys like Doolittle were looking with binoculars for pilots from the Eagle Squadrons – we had combat experience, and with dogfighting.

“The decision was made that the three Eagle Squadrons would transfer over to the Eighth Air Force. I figured that they were not going to take me, as I was not an American. Well, Peterson was the liason officer between the RAF and the Eighth Air Force and he said that they needed every one of us, including me. Well, I went to London to be interviewed, facing three Army Air Force colonels.

“They asked if I lived in America and I said ‘yes sir’ and explained how the RAF had trained me in California. They asked if I intended to go back to America and I answered ‘yes sir’. They asked if I would accept a commission in the United States Army Air Force and that they needed every one of us. I just couldn’t believe it.

“So, I was practising dogfighting with my room mate Gentile in our P-47s. We had to get 30 hours in the aircraft to be considered combat-ready. Over the radio, I was ordered to return to base immediately. There was a staff car waiting for me with Chesley Peterson at the wheel, I was afraid that an order had come from the Greek wing commander that they had to have me in the Greek Air Force.

“Well, the Group Commander Colonel Anderson told me to sit down and called the ambassador at the American Embassy. Now I was afraid they were going to tell me that I could not stay in the air force. Well, the ambassador asked me ‘lieutenant, how would you like to become an American citizen? There is a special envoy from Washington who is here to naturalize about half a dozen of you boys, and we want you to be the first one’.

“I looked at Peterson and he was smiling like nobody’s business. He asked if I was surprised. ‘Surprised? You almost gave me a heart attack, the Greeks wanted me to go to Egypt, I said’.

“On March 3, 1943, because of a recent Act of Congress, Steve Pisanos became the first individual ever in American history to be naturalized as a US citizen outside the borders of the United States.

“Walter Cronkite was there, Ed Murrow was there, Andy Rooney was there… oh my God, Ed Murrow came up to me with that cigarette in his mouth and said ‘lieutenant, what took place this afternoon in this room, I’m going to relate to the American people tonight’.”

America had a new fighter pilot, forever to be known as ‘the flying Greek’. Now flying the P-47 for the Americans in Squadron 334, Pisanos was to become an ace with six confirmed victories.

He said: “My first victory was on May 21, 1943, over Belgium. I got on this Fw 190’s tail and I blasted him. Once, over Belgium, I came down on this damn 109. We found ourselves on the deck and I was still on his tail trying to get into position when out of the corner of my eye I saw these high tension wire towers. Knowing the area, this gentleman was trying to get me to fly into these wires, so I raced my P-47 and barely missed the top wire and got him on the other side.

“I made my report and they went to my aircraft and got the film. The film was completely blank. As far as I’m concerned, I killed that son of a bucket; he blew up right in front of me.”

Steve got no official credit, although he still ended the war with 10 confirmed victories, six with the P-47 and four with the Mustang – a double ace. By 1944, he was to receive a P-51B.

He said: “It was the first one with the Rolls-Royce engine, but it did not have the bubble canopy. It was a good aircraft and I went on the first Berlin mission on March 3, 1944. After the war, I sat next to Adolf Galland at the Paris Air Show. He asked me ‘what kind of airplanes did you fly?’ I told him ‘I don’t fly any more general, but in the war I flew Spitfires with the 71 Eagle Squadron’.

“When I said ‘Spitfire’ I think he went about four inches up in the air. He said ‘my friend… that was Colonel Blakeslee’s organisation, the Fourth Fighter Group, 1016 victories. We knew him well in the Luftwaffe; he was one of the greatest aerial commanders. You know, when we learned that (Hubert) Zemke was shot down, I was in Berlin that day and told the marshal that if we could get this fellow (Don) Blakeslee, our problems with the Americans would be over’. Truthfully, looking back, they were the two greatest commanders we had, Zemke and Blakeslee.”

Blakeslee was grounded in September 1944, and it has been said that he flew more missions than any other American pilot of the war. By then, Steve Pisanos was similarly out of action, through entirely different circumstances. On May 5, 1944, while on a return flight after logging additional victories against Bf 109s while flying bomber escort, Pisanos was forced down behind enemy lines with mechanical problems.

Ironically it had been the same day that future aviation legend Chuck Yeager was shot down further south in France. Steve joined up with the French Resistance and participated in missions against the occupying German forces until that summer when the Allied armies reached his position in Paris. In 2010, he received the French Legion of Honor in a ceremony held in San Diego to honour his service as both a fighter pilot in the skies over France and his later efforts with the French Resistance.

Steve said: “I’ve been asked ‘of the aircraft that you flew, which one did you prefer?’ Well, the Hurricane was a good aircraft and if you recall your history, during the Battle of Britain it got more victories than the Spitfire. After I flew the Hurricane my instructor in the operational training unit (before Pisanos joined the 268 Squadron), who had 13 victories in the Battle of Britain, asked me, ‘how did you like it?’ I said that it was the best fighter I had ever flown. His response was ‘wait until you fly the Spitfire’.

“If you wanted me to defend San Diego against enemy bombers or what-have-you I’ll take the Spitfire. For aerial combat, the Spitfire was number one. Now if you wanted me to intercept a train full of enemy soldiers, east of San Diego, I’ll take the P-47. If you wanted me to escort bombers up to San Francisco, I’ll take the Mustang.”

After the liberation of Paris, Pisanos was transferred back to the United States for his new role as test pilot.

He said: “In October 1944, after I had returned from France, I went to the Park Hotel in New Jersey to see my friends there. You have no idea – the entire hotel staff had come out to see Lt Pisanos who had come back from the war with 10 victories. They had a big dinner, the mayor, the chief of police, even the mayors from the surrounding cities were there – unbelievable.

“They wouldn’t let me fly again in France, so they sent me to Wright field to test enemy aircraft – the Me 262, the radial Fw 190s, the Bf 109 and the Zero. I was a test pilot along with my good friend Don Gentile. Then, after the war, it was Chuck Yeager, Bob Hoover and me. When Colonel Bill Councill set the records in the Shooting Star going from West to East, actually I was supposed to fly the thing. I had like 100 something hours in the YP-80 program.”

He was later to be involved in the testing of other planes, such as the Delta Dagger and after further service flying in Vietnam, Colonel Pisanos retired in 1974.

Steve said: “The Eagle Squadron Association made up of those of us who served in the Eagle Squadrons 71, 121, and 133 – we made this museum, the San Diego Air & Space Museum, our home. Back in 1980-something, the president said ‘you know, we don’t have a Spitfire’. So, we prepared a letter and sent it to the Air Ministry. An Air Marshal came right back and said that ‘we have a Spitfire for you boys, but we need a favour, we don’t have a Mustang for our museum’.

“Where on earth were we going to get a Mustang? So, what we decided to do was to collect parts of a Mustang. We got the propeller from Australia, the engine from San Francisco, a wing from a Mustang that had crashed… well, we got this fellow with a big garage in El Cajon, and he knew about putting airplanes together.”

There were huge challenges ahead for the Eagles. Steve said: “The biggest guy who helped us was the President of Federal Express, Fred Smith. He gave us $50,000. So, we put the Mustang together and went to the air force and asked them, but some guy came back and said ‘we can’t do it, if Congress finds out we’ve done this, they’ll raise the dickens’. So, it was back to our friend Fred Smith.

“He sent a 747 to Miramar where we loaded the Mustang into boxes after we took it back apart and flew it to England. They got the Spitfire and brought it back.”

That Spitfire now sits next to the Eagle Squadron display at the San Diego Air & Space Museum. Steve Pisanos has had a long life and an incredible adventure.

“Of course, this is a wonderful country,” he said. “It is a country that believes in freedom, opportunity, equality and promise, and that’s exactly what Uncle Sam did for me.” One might add ‘with a little help from the Royal Air Force’.