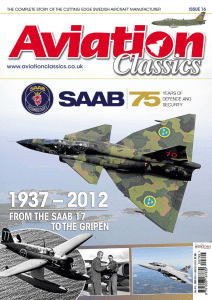

Welcome to the first of what I hope will be a succession of different Aviation Classics, one where we are not covering a single type of aircraft or an event, but instead studying the entire history of one of the great aircraft manufacturers. The choice of Saab for this first issue came about due to a number of factors.

Welcome to the first of what I hope will be a succession of different Aviation Classics, one where we are not covering a single type of aircraft or an event, but instead studying the entire history of one of the great aircraft manufacturers. The choice of Saab for this first issue came about due to a number of factors.

Firstly, 2012 is the 75th Anniversary of the founding of what is now a world class giant of the aerospace industry, and secondly, on looking around, I could find very little that covered the history of the company and its highly original products, a situation I found odd. My interest in Saab and its aircraft began at an early age, when as a boy I built the Airfix kit of the mighty Viggen.

Placing it among the Phantom, Lightning and other types of its generation, two things became apparent, first of all this was a really big aircraft, and secondly, it didn’t look like anything else around, and indeed, still doesn’t. I was struck by the individuality of it, and this is an impression that has stayed with me even as I have learned more about this company and the country where it was founded.

Sweden and Saab have a number of things in common, they are both defined by contrasts. Sweden is the third largest country in Europe, yet has a smaller population than Greater London. It is a fiercely neutral country, defending its right to stay out of other nations’ conflicts and remaining strictly non-combatant in the Second World War, yet at the height of the Cold War boasted the fifth largest air force in the world, one with capabilities and equipment standards few could match and none surpass.

Saab has built military aircraft from its formation, yet its prime ethos is purely defensive, a sincere wish that everyone should have the right to feel safe. Saab is a commercial company, but over 20% of its income is ploughed back into research and development and there is a massive investment in education throughout the country.

This company ethos is an echo from the nation’s history, from 1612 and a man called Axel Oxenstierna. He was Lord High Chancellor of Sweden and between 1612 and 1640 he oversaw what can only be called the modernisation of Sweden. Oxenstierna began the development of trade and industrial policies and developed a strong central administration, both local and national, that brought efficient organisation where before there had been chaos.

Part of this Government reform began at grass roots level, with the development of a system of higher education that allowed anyone, not just the sons of noblemen, to progress to high office. He saw education as the key to the development and the future of the nation; that people should be encouraged to think. Pope Urban VIII declared that Oxenstierna was one of the most excellent men the world had ever seen.

How then are the works of this man reflected in Saab and its ethos? Well, it

too has organised much of the aerospace and defence industry of Sweden into an efficient core. It has encouraged education at every level, beginning with one of the first trade training apprenticeship schemes in the world. It certainly encourages people to think, as Börje Fondén told me when we were discussing the development of the Viggen.

He said: “We didn’t have 30 engineers working on the project; we had 30 inventors working on it! Inventions were allowed to work in our system, regardless of where they came from.”

This respect for the inventiveness of their staff has allowed Saab to develop some of the most high performance and ground breaking aircraft in the history of aviation, it has also gained the company a reputation as a world leader in aerospace technology.

In 75 years, a company that began working alone due to political circumstance is now working both in and with 30 other countries across the globe. What it has produced in this time has been of unrivalled quality and innovation. I look forward to seeing what they achieve next, because no doubt it will be both original and surprising.

In 75 years, a company that began working alone due to political circumstance is now working both in and with 30 other countries across the globe. What it has produced in this time has been of unrivalled quality and innovation. I look forward to seeing what they achieve next, because no doubt it will be both original and surprising.

Happy birthday Saab!

All best,

Tim

Contents

Contents

8 Saab – the genesis of a giant

18 The first Saab

24 The Swedish Mosquito

28 Innovative and unusual

34 The Saab 90 Scandia

36 Light delight – Saab 91 Safir

38 Survival through diversity – the first Saab cars

40 Perspectives – Saab, Sweden and the Swedish Air Force in the Cold War

44 Swept wing success – Saab 29 Tunnan

52 Systematic elegance – Saab 32 Lansen

60 Supersonic double delta – Saab 35 Draken

70 Twin jet trainer – Saab 105

74 Swedish style

80 Loud and proud – Saab 37 Viggen

90 Piston trainer – Saab MFI-17 Supporter

94 Airliner and AEW – Saab 340 and 2000

10 2Fifth generation fighter – Saab JAS 39 Gripen

110 Into the future

112 The Flygvapenmuseum

126 Survivors

Twin jet trainer – The Saab 105

It served as a jet trainer, light ground attack aircraft, reconnaissance platform and four seat communications aircraft, yet the Saab 105 began life as a concept for a business jet.

It served as a jet trainer, light ground attack aircraft, reconnaissance platform and four seat communications aircraft, yet the Saab 105 began life as a concept for a business jet.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Saab began considering the civilian market again, this time with a view to building a small, high speed business jet. There were a number of concepts studied, including a very advanced delta winged five seat aircraft. At the same time, towards the end of 1958, the Swedish Air Force began considering a replacement for the de Havilland Vampire J 28C trainers then in service.

With the J 35 Draken beginning to enter service, the Vampires were no longer adequate trainers to introduce pilots to flying supersonic jets. The Swedish Air Force was evaluating a number of foreign designs, such as the British Hunting Jet Provost and the Canadair Tutor to fulfil the requirement, but was keen to buy a domestically produced aircraft.

Saab was well aware that the military market was far larger than any potential civil sales of a light jet, so it modified the light jet concept to a more conventional design, launching the Saab 105 in April 1960. Under project manager Ragnar Härdmark, the design evolved to become a high winged, twin engined aircraft with the instructor and pupil seated side by side under a large, single piece canopy.

The new trainer was to be powered by a pair of Turboméca Aubisque low bypass turbofans of 1635lb (7.49kN) thrust each, given the designation of RM9 in Swedish Air Force service in line with previous engines. On December 16, 1961, the Air Board approved the continuance of the design project, with the proviso that the trainer could also act as a ground attack aircraft. This was followed in April 1962 with a preliminary contract for the purchase of 130 aircraft should the design meet the performance requirements.

Construction of two prototypes began immediately after this, with the first flight taking place on July 1, 1963, with test pilot Karl-Erik Fernberg at the controls. Early test flights revealed a number of aerodynamic problems with the air intakes and engine exhausts, both of which required extensive modification. This also affected the wing root design, beneath which the engines, intakes and exhausts were situated, so it was not until June 17, 1964, that the second prototype made its maiden flight.

However, the modifications to the first aircraft had proved satisfactory prior to this, so in March 1964 the Government had approved the purchase order for the aircraft now designated SK 60. The original order was increased to 150 aircraft in August 1965, the same month that the first production aircraft flew for the first time.

The Swedish Air Force Flying School at Ljungbyhed, also known as F 5, received its first SK 60As in April 1966. Initial problems were experienced with engine reliability, but these were corrected through an extensive modification programme. On July 17, 1968, the first student pilots began training on the aircraft, with all 149 production versions of the type delivered by 1968. Once the type was in service, a series of modification programmes were carried out on the aircraft, resulting in four sub types.

The first of these was the SK 60B, a ground attack version of the trainer which was fitted with up to six underwing pylons for weapons and a Ferranti F-105 integrated strike and interception system (ISIS) multifunction sight in front of the port seat. Around 60 aircraft were modified to this standard from 1970 onwards and their pylons could carry a pair of pod mounted 30mm Aden cannons, two 12.7mm machine gun pods for gunnery training, bombs up to 550lb (250kg), 12 5.3in (13.5cm) rockets or six 5.7in (14.5cm) rockets. None of the pylons could carry external fuel tanks.

A single prototype of the next version of the Saab 105 was built, flying for the first time on January 18, 1967. This was the SK 60C, which was intended to be an enhanced light strike version which could also perform reconnaissance and forward air control missions.

These aircraft had an extended nose which housed a Fairchild KB-18 panoramic camera and an infrared search unit. The SK 60C could also carry a photoflash pod on one of the wing pylons to carry out night photography. Including the prototype, which was the 150th and last Saab 105 delivered to the Swedish Air Force, 30 aircraft were converted to SK 60Cs from both A and B variants. A number of SK 60Cs later had the camera port faired over as the reconnaissance role was taken over by other types.

Saab had also designed the 105 from the outset to be capable of operating as a four seat liaison and communications aircraft, a feature harking back to the design’s origins as a light business jet. The two Saab ejection seats could be quickly removed and replaced with four airliner type seats which had no provision for wearing parachutes but were at least comfortable, or four rather more military seats which did allow for the wearing of parachutes. During the mid-1970s, 10 aircraft were permanently modified as four seat transports and designated as SK 60Ds.

A small number of four seat Saab 105s were equipped with commercial civilian instruments and an instrument landing system (ILS). These were known as SK 60Es, and were used to train Air Force Reserve pilots in flying commercial aircraft. All of the E versions were eventually used in the same role as the SK 60Ds, as light transport and liaison aircraft. All of these modification programmes were carried out by the air force’s central maintenance and repair centre, the CVM.

Saab had been working on a replacement for the Saab 105, the B3LA, but this project was cancelled in 1979. In 1988, a structural upgrade programme was carried out on the 142 SK 60s of all versions still in service, to keep the aircraft in service for as long as possible. This included new wings and other structural strengthening and modified ejection seats. This structural programme was extended still further in 1993, when 115 SK 60As, Bs and Cs were fitted with a pair of the Williams Rolls FJ44 turbofans.

These engines produced 1900lb (8.45kN) of thrust each, but were not only more powerful, they were also quieter, cleaner, burned less fuel and were much easier to maintain. The aircraft were also fitted with a fully automatic digital engine control (FADEC) system which enhanced the fuel efficiency of the engines and gave them what is known as ‘carefree’ handling.

The four seat SK 60D and E models were not given this upgrade, instead these aircraft were grounded and used as spares for the remainder of the fleet. The SK 60 is still in service today as an advanced pilot trainer, a remarkable record of service for this type of aircraft. That so many of the original fleet of 150 were still available for upgrade 27 years after their introduction is nothing short of amazing. Military trainers and ground attack aircraft are very hard used machines, so this record speaks volumes about the 105’s inherent toughness and reliability.

Aside from the Swedish Air Force, the Austrian Air Force also acquired the Saab 105, but a much modified variant. On April 29, 1967, Saab made the first flight of the 105XT, an export version modified from the second prototype. This was fitted with the much more powerful General Electric J85-GE-17B turbojets which produced 2845lb (12.6kN) of thrust. These engines meant the 105XT could carry a much heavier load of external stores, 4410lb (2000kg).

The internal fuel tanks were increased in size from 308 gallons (1400 litres) to 450 gallons (2050 litres), and provision was made for the carriage of two 110 gallon (500 litre) drop tanks on the inner wing pylons. The XT could also carry the AIM-9J Sidewinder air to air missile. The wing was strengthened to accommodate this greater weight, and to absorb the increased performance stresses the engines also gave the aircraft.

In 1968, the Austrian Air Force ordered 20 of these modified aircraft, designated Saab 105Ö, and followed this with an order for 20 more the following year. These 40 aircraft were all delivered between 1970 and 1972, replacing the Saab J 29 Tunnans still in service in Austria. The 105Ös were used to fill the training, reconnaissance, close air support and air defence roles, being fitted with a specially designed Vinten camera pod under one wing and a photoflash pod under the other to fly day and night reconnaissance missions.

In 2010, 12 of these aircraft underwent a life extension programme aimed at keeping them in service until at least 2020. Both Switzerland and Finland were offered modified export versions of the Saab 105, but both sought solutions in other aircraft types. The second prototype was modified once again in 1972 to become the sole example of the Saab 105G. This was fitted with a comprehensive navigation and attack system, but it attracted no orders. However, the second prototype remained in service as a flying testbed and trials aircraft until 1992 when it was retired to a museum.

The Saab 105 did not attract the same attention as the supersonic fighters and other types that Saab produced, but it was no less an impressive aircraft for that, reliable and enduring. It also earned a special place in the hearts of the Swedish and Austrian people as the mount of their national aerobatic teams, the Swedish ‘Team 60’ and Austrian ‘Karo As’ and ‘Silver Birds’.

The first Saab

The first Saab

A single engined bomber, dive bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. SAAB had been formed on April 2, 1937, at Trollhättan by the Bofors group. In 1938, ASJA had begun design work on the L-10, a multi-purpose single engined military aircraft at its factory at Linköping. When ASJA and Saab underwent a complete reorganisation and merger in March 1939, the new company’s first aircraft, which had been the L-10, became the Saab 17.

A single engined bomber, dive bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. SAAB had been formed on April 2, 1937, at Trollhättan by the Bofors group. In 1938, ASJA had begun design work on the L-10, a multi-purpose single engined military aircraft at its factory at Linköping. When ASJA and Saab underwent a complete reorganisation and merger in March 1939, the new company’s first aircraft, which had been the L-10, became the Saab 17.

The Air Board offered a new competition to ASJA and SAAB in early 1938 to design a reconnaissance aircraft for operation by the air force. A particular requirement was good visibility from the observer’s cockpit.

The new aircraft was to have a maximum speed of at least 250mph (400kph). The joint company run by both Saab and ASJA, AFF, produced a design for a high wing aircraft with an undercarriage that retracted into stub wings mounted low in the fuselage. These stub wings proved aerodynamically problematical, so a fixed undercarriage was substituted, resulting in an aircraft not unlike Westland’s Lysander. Needless to say, this aircraft, known as the F-1, stood little chance of meeting the design criteria and was cancelled.

It was the cancellation of this project that increased the rivalry between Saab and ASJA and proved that collaborative efforts, no matter how desirable to the Swedish Government, were unlikely to succeed. ASJA would have been the company that actually built the F-1 had it gone forward, but its evaluation of the design and its likely performance revealed its shortcomings. ASJA entered its own design into the competition, known as the L-10, and it succeeded where the F-1 could not.

This served only to increase the mistrust between the two companies. At this point, one of the most important men in the founding of Saab took a hand. Torsten Nothin was a former member of parliament and chairman of the joint company AFF. At the December 1938 board meeting, he introduced the view that the collaborative company was not the right way forward for any of the participants, and asked for suggestions as to how the situation could be resolved. These were received in January 1939 and after a series of negotiations, a complete restructuring of both ASJA and Saab resulted in a new single company emerging in March.

The new Saab was wholly owned by ASJ, the parent company of ASJA, and had its headquarters at Linköping. The Trollhättan factory was to be for production only, all design and development taking place at Linköping under the direction of managing director Ragnar Wahrgren. For his efforts to reach a workable solution and his far reaching vision of the needs of future aircraft production, Torsten Nothin was voted in as chairman of the board of the new Saab company.

As has already been mentioned, prior to these historic events ASJA had begun design work on the L-10 for the reconnaissance aircraft competition. This was a remarkably advanced and adaptable design for the time, and was to be the beginning of Saab’s reputation for innovation and unusual design features. Firstly, ASJA had convinced the Air Board that if the new aircraft could function as a bomber and a reconnaissance aircraft for the army and navy, then it would save a great deal of money.

Crews would only have to be trained on one type for both missions and there would be tremendous economy of scale to be achieved in having one set of spares for both forces while the aircraft was in service. There would also be a saving in production costs as more of the new design would be built for both roles, thus bringing down the unit cost. These suggestions were applauded by the Air Board which immediately understood their advantages.

For the L-10, the Linköping design team decided on an internal bomb bay in the fuselage resulting in a mid-wing design. This did not give the observer the perfect view from the aircraft, but it was decided that the advantages in the multi-role design far outweighed this one disadvantage. The aircraft was designed for dive as well as level bombing and featured an innovative dive brake. The main undercarriage retracted upwards and backwards where it was enclosed by a large fairing. This meant that there were no bays in the wing to accommodate the undercarriage, increasing the structural strength of the centre section. These fairings also made excellent aerodynamic brakes when the undercarriage was lowered in a dive.

To give the aircraft as much flexibility of operation as possible, it was designed from the outset with a retractable ski undercarriage option as well as a float design, both of which were interchangeable with the wheeled undercarriage. The Air Board reviewed the design and the engineering mock up that had been built, and on November 29, 1938, issued an order for two L-10 prototypes.

With the reorganisation of the two companies, the L-10 was later named the Saab 17 and work continued on the production of the two prototypes. However, the Second World War began on September 1, 1939, and was to delay the programme for a number of very different reasons. Firstly, the Swedish armed forces were desperately short of modern combat aircraft, so they were seeking supplies from all over the world. These aircraft were often supplied disassembled, so they required factory time to prepare.

Secondly, the supply of engines, parts, drawings and other critical components from manufacturers abroad became nigh on impossible to acquire. Lastly, experienced engineers and draughtsmen were in very short supply. By 1940, Saab had only two thirds of the required number of these critical workers employed on the new aircraft. Indeed, the full complement of 600 trained engineers was not to be met until 1943. This situation was further exacerbated by the fact the Saab 17 was the first all metal, stressed skin aircraft designed in Sweden, increasing the pressure on the new company.

Then, on November 30, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Finland requested Sweden’s help in acquiring new aircraft, bringing them in from orders placed abroad, assembling and equipping them, and then delivering them to Finland. Saab assembled 44 Brewster Buffaloes and 17 Fiat G.50s for Finland, taking up most of the production capability at Trollhättan among other factories during the Winter War.

When Germany invaded Denmark and Norway on April 9, 1940, Sweden suddenly found herself cut off from the world. As part of Swedish efforts to assist Finland in the Winter War, a force of Swedish Air Force crewed Gloster Gladiators and Hawker Harts, or J 8s and B 4s as they were known in Swedish service, had been sent to Finland. Known as Flygflottilj 19 or F 19, this force was to destroy 12 Soviet aircraft and attack a wide variety of ground targets during the conflict.

Since Germany was acting in concert with the Soviet Union under the terms of the non-aggression pact of August 1939, they now viewed Sweden with suspicion and withdrew all supplies of aircraft and other weapons while the war in Finland continued. On the Allied side, initial orders from the United States for hundreds of aircraft like the Seversky P-35 and Vultee P-66 Vanguard were approved. Neither Britain nor the United States were willing to supply more modern types, especially fighters, and the US Government had decided to concentrate on supplying Britain and France as its priority for new aircraft.

Then Sweden’s neutral position and ability to withstand pressure from the Soviet Union and Germany were called into question in the US. Worse was to come, as on July 2, 1940, defence exports to Sweden from the US were prohibited and all stocks of aircraft awaiting supply were confiscated. With the aircraft also went the spare engines that had been ordered. Negotiations to build the Pratt and Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp and R-2800 Double Wasp under licence in Sweden were also broken off. Only Italy had aircraft it was willing to supply, but these were not up to current operational standards. Suddenly Sweden found herself critically short of modern aircraft and engines, surrounded by hostile and potentially hostile forces and abandoned by the Allies.

As a historical footnote to this situation, if you have ever wondered why Sweden has remained completely self sufficient in aircraft and weapons production, building up the industry and technology base to a point where she is now a major exporter of world class aircraft and systems, this shoddy treatment of the country by the Allies is the starting point.

Self sufficiency was the only course of action left open to Sweden if she was to maintain her neutral position. Given the situation, Sweden’s reaction for the remainder of the Second World War was one of resilience to all pressure and coercion from both Allied and Axis Governments.

To return to the story of the Saab 17, work continued on the prototypes around all the other rushed activities the wartime situation created. On May 18, 1940, the first of the two prototypes made its maiden flight at Linköping in the hands of test pilot Captain Claes Smith. The first aircraft was powered by a Bristol Mercury XII built under licence in Sweden by Nohab. This produced 860hp, which was changed in the second aircraft to a 1065hp Pratt and Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp.

The flight test programme was not without incident, on the first flight the cockpit canopy blew open in the airflow. Smith held onto it for as long as he could, but needed both hands for the landing. It detached and landed in a meadow where it was later recovered. A more serious problem was found during the spinning trials. The engine often stalled on spin entry and recovery was found to be difficult, requiring full control deflection.

Attaching lengths of wool to the tailplane enabled an observer aboard an accompanying aircraft to record the turbulent airflow over the rudder, the problem being solved by the addition of a small fin under the rear fuselage. Other than these two small problems, the new aircraft proved to be a reliable and steady performer, possessed of pleasant handling and an ease of maintenance that drew favourable comment from service personnel.

The bomb load of the Saab 17 was 1540lb (700kg) which could be made up of a wide variety of weapons. The largest that could be accommodated in the internal bomb bay was a 525lb (250kg) bomb. Three 8mm machine guns were fitted, two in the wings and one on a flexible mount in the rear observer’s cockpit. One of the great innovations developed while the Saab 17 was in production was a new ‘toss’ bombsight, the BT 2, which had been developed by two Saab engineers to solve the problem of aiming bombs during a dive.

Erik Wilkenson and Torsten Faxén essentially created a one of the first mechanical computers in the world, enabling crews to deliver bombs with tremendous accuracy in relatively shallow dives of between 20 and 30 degrees. Aside from the accuracy the sight gave the crews, it also meant they could remain at medium altitude, minimising their exposure to ground fire. The sight also provided for automatic separation between the aircraft and the bomb on release. Postwar, this sight was developed into an electro-mechanical version called the BT 9 which was used on later Saab aircraft and sold to France, Denmark and Switzerland. It was also produced under licence in the United States and was the first Saab system to be exported.

On December 1, 1941, the first production Saab 17 took to the air, the first of 324 built, 57 at Linköping, the remainder at Trollhättan. Deliveries to the Swedish forces were to continue until September 16, 1944, of which 133 were B 17As, 114 were B or S 17Bs, 38 of which were delivered as seaplanes designated the S 17BS, followed by the last model, 77 of the B 17C.

The major difference between the three versions was the engine, the 17A being fitted with the Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp, the 17B with the Bristol Mercury XXIV and the 17C with the Piaggio PXI. To explain the Swedish military designation system, the first letter designates the role of the aircraft, B being bomber, S for reconnaissance, J for fighter, SK for trainer and A for ground attack. This was followed by the number identifying the aircraft type, then the letter of the version.

The Saab 17 proved to be both popular and incredibly reliable in service. In Swedish Air Force service it equipped six wings in its bomber and reconnaissance roles, F 2, F 3, F 4, F 6, F 7, and F 12. It was only retired as a front line aircraft with the advent of jet aircraft, the last leaving service in 1948. As the Second World War ended, 15 B 17Cs were allocated to the Danish Brigade, made up of expatriate Danish military personnel and first formed in Sweden in 1943.

This force was intended to deploy to Denmark in the event the German forces there refused to accept the surrender, but this eventuality never arose. The Saab 17 got a new lease of life in 1947, when the first of three batches of 47 B 17As were supplied to the Ethiopian Air Force, a service that had been formed with the assistance of Swedish Air Force personnel at the request of Emperor Haile Selassie. The tough and reliable Saab 17 was ideally suited to operations over the massive and harsh country, and was to remain in service long after more advanced aircraft were intended to replace it. The last were not retired from front line service in Ethiopia until 1968, and a small number were kept on to perform secondary duties into the 1970s, a remarkable record by any standards.

The last Saab 17s flying on operations in Europe were used as target tugs. In Sweden, the first of 20 B 17A aircraft were released onto the civil register in 1951 for use by two companies, Svensk Flygtjänst and AVIA, who supplied target towing facilities to the Swedish military. One of these aircraft was sold to the Austria Air Force in 1957 to fulfil the same role there, followed by two more to the Finnish Air Force in 1959 and 1960.

Considering this was the first aircraft designed and produced by the new Saab company, and the first advanced all metal aircraft produced in Sweden, its track record is exemplary, and set the performance and reliability standards for which Saab is rightly still famous today.