Called the ‘Great War’, it was a name which described the extensive destruction and impact it left on the world. Highlighting the mass carnage of World War One, when the Battle of the Somme began at 07:30 on 1 July 1916 – following a brief and eerie silence as tens of thousands of men considered their fate in the next few minutes – whistles blew and the first British and French infantrymen left their muddy trenches to meet a deadly hail of machine-gun fire.

Called the ‘Great War’, it was a name which described the extensive destruction and impact it left on the world. Highlighting the mass carnage of World War One, when the Battle of the Somme began at 07:30 on 1 July 1916 – following a brief and eerie silence as tens of thousands of men considered their fate in the next few minutes – whistles blew and the first British and French infantrymen left their muddy trenches to meet a deadly hail of machine-gun fire.

By the end of this first day the British alone had almost 20,000 men killed, over 35,000 wounded, more than 2000 missing and hundreds more taken prisoner – the total loss was almost 60,000 in just one day and the offensive was to go on until November.

Above the devastation of the trenches, a new form of warfare had been rapidly evolving in the air which was transforming military strategy. Planning for the Somme offensive was based on the aerial reconnaissance photographs provided by the Royal Flying Corps. ‘Winged’ warriors were now duelling in the sky, which was their very own field of honour where they often fought by a gentleman’s code that would seldom be repeated in modern warfare. This chivalry in the air contrasted with the slaughter below, although war it still was and many young and inexperienced airmen were killed within days of their arrival on the front line. During the months of the Somme offensive almost 800 aircraft were lost, taking with them the lives of hundreds of airmen. These early flyers certainly played their part in the eventual Allied victory.

Flying in fragile fabric-covered aircraft, being shot at from the air and ground and without parachutes, the risks were high. There are some incredible stories of courage from this period though, as is evident with those of Alan Arnett McCleod and Albert Ball who both feature in this issue of Aviation Classics.

As a boy I became fascinated with the aerial conflict of World War One after watching classic films such as The Blue Max and Aces High. I built models of an all-red Albatros and Sopwith Camel and remember spending hours on the stairway landing playing out dogfights between the two. Later I read much about the exploits of the daring early military airmen of the era and was often left in awe of their bravery and achievements in the line of duty. It only further fuelled my desire to join the Royal Air Force, which had been established during this conflict on 1 April 1918.

Today’s airshow audiences can see this aspect of the evolution of military aviation well represented the world over. For example, in the UK the Shuttleworth Collection has a wonderful fleet of 1914-1918 period machines. In the USA there are numerous airworthy World War One types at Old Rhinebeck. Over in New Zealand The Vintage Aviator Ltd has in the past few years made great progress with both the restoration of original aircraft and the multiple construction of perfect reproductions of types from the era.

I was invited out to witness the results and the reproduction Albatros D.Va that was about to fly particularly caught my eye. It has been built to exact specifications and is powered by an original engine, so is as close to seeing an original Albatros D.Va fly as can be. Add to that TVAL’s superb Sopwith Camel and it all brings to life those model dogfights of my youth.

I’d very much like to thank the following at TVAL for all their assistance and kindness in many ways during my visit to gather material for this issue: Gene DeMarco, Tim Sullivan, Stuart Goldspink, Keith Skilling, John Bargh, Gary Yardley, David Cretchley and – last but certainly by no means least – camera ship pilot Kerry Conner. Without their passion to showcase these wonderful aircraft to a wide audience this issue would not have been possible.

I’d very much like to thank the following at TVAL for all their assistance and kindness in many ways during my visit to gather material for this issue: Gene DeMarco, Tim Sullivan, Stuart Goldspink, Keith Skilling, John Bargh, Gary Yardley, David Cretchley and – last but certainly by no means least – camera ship pilot Kerry Conner. Without their passion to showcase these wonderful aircraft to a wide audience this issue would not have been possible.

Jarrod Cotter

Editor

Contents

Contents

6 Introduction

8 Founding the Royal Flying Corps

12 ‘Day One’ of the RAF

18 For Valour

20 ‘King of the Air Fighters’

24 Sopwith Camel cockpit

25 Sopwith works

26 The Camels that came over water

30 London’s first ‘Blitz’

32 Still on the front line

34 The ‘Mount of Aces’

42 The ‘Red Baron’

46 ‘Flying Circus’ Triplanes

50 Absolute authenticity

52 ‘Hun chivalry’

54 Albatros D.Va sepia photograph

56 America’s ‘Ace of Aces’

60 ‘Biff’

62 Flying with Daedalus

66 First to France

Watch Video70 Innovation on the Western Front

74 The gods above must be crazy…

82 Nottingham’s aerial warrior

88 The infancy of American air power

96 Britain’s first aerial defenders

98 First Zeppelin raid on the British Isles

102 Battle for the Suez Canal

110 Shuttleworth’s World War One ‘squadron’

114 Short Admiralty Type 184

116 ‘Bloody Paralyser’ Type Os

118 ‘Fee’

120 ‘Father of the RAF’

124 Deadly Albatros

128 Albatros D.Va cutaway

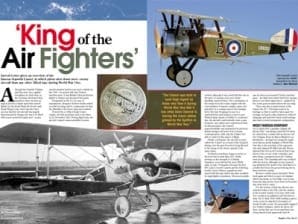

King of the Air Fighters

A special preview feature from Aviation Classics – Knight of the Sky – Jarrod Cotter gives an overview of the famous Sopwith Camel, in which pilots shot down more enemy aircraft than any other Allied type during World War One.

A special preview feature from Aviation Classics – Knight of the Sky – Jarrod Cotter gives an overview of the famous Sopwith Camel, in which pilots shot down more enemy aircraft than any other Allied type during World War One.

Although the Sopwith Triplane and Pup were very capable aeroplanes for their time; as the Germans developed their machines, there became an urgent need for a faster and better armed fighter for the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Flying Corps. Such was the Pup’s success that the new aircraft was largely based around its design, but was to be fitted with a more powerful engine and – as gun synchronisation had become more reliable by late 1916 – be armed with twin Vickers machine guns. It was Britain’s first production fighter to feature synchronised twin guns.

Designated as the F.1, for ease of manufacture, designer Herbert Smith settled on a flat top wing; and to compensate for that, the dihedral of the lower wing was doubled.

Powered by a 110hp Clerget rotary engine, the first prototype took to the skies on 22 December 1916. During flight tests, the aircraft’s superb manoeuvrability became evident, although it was noted that this was at the price of causing some very tricky handling characteristics. The combination of the torque from the rotary engine with the concentration of masses (engine, guns, fuel and pilot) in a compact area of the fuselage led to the type dropping its nose in a starboard turn and rising in a turn to port. Without large inputs of rudder to counteract this, the aircraft could violently enter a spin. However, once pilots were experienced with its idiosyncrasies, the Camel’s manoeuvrability was unmatched by previous British designs and most of its German contemporaries, with only the Fokker Dr.I able to rival it in this aspect of flight.

Firstly a nickname, the aircraft became called the ‘Camel’ as a result of the humped fairing over the gun breeches being likened to the hump of the desert animal of the same name.

Production machines began to arrive on the front line in early May 1917; firstly arriving on the strength of 4 (Naval) Squadron, soon followed by more RNAS units. In July, 70 Squadron became the first RFC unit to receive Camels and the following month, Home Defence squadrons were issued with the type which was later modified for night-fighter operations. This most notably saw its twin nose-mounted Vickers machine guns – the flash from which had been causing pilots to lose their night vision – replaced by two Lewis guns mounted above the top wing.

There was also a naval version of the Camel, the 2F.1. This had a joint in its fuselage so that it could be taken apart for stowage on board a ship, featured a reduced wingspan and narrower track undercarriage, plus had a revised armament configuration.

Most famous dogfight

On 21 April 1918, Canadian Captain AR Brown DSC* was flying Camel B7270 when he entered into combat with an all-over red Dr.I Triplane flown by Baron Manfred von Richthofen – perhaps becoming the single most famous aerial dogfight of World War One due to the notoriety of his opponent, who had claimed 80 Allied aircraft. Brown attacked the Dr.I as he’d noticed that it was about to fire on one of his comrades, and after firing a sustained burst the Triplane went down. The Canadian pilot was credited with the victory, although recent research has attributed the death of the ‘Red Baron’ to a bullet fired from the ground during the by then low-level combat.

Brown’s combat report included: ‘Went back again and dived on pure red triplane which was firing on Lieut May. I got a long burst into him and he went down vertical and was observed to crash…’

For the actions of that day, Brown was awarded a Bar to his DSC, and the citation in the London Gazette of 21 June 1918 read: ‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. On 21 April 1918, while leading a patrol of six scouts he attacked a formation of twenty hostile scouts. He personally engaged two Fokker triplanes, which he drove off; then, seeing that one of our machines was being attacked and apparently hard pressed, he dived on the hostile scout, firing all the while. This scout, a Fokker triplane, nose dived and crashed to the ground. Since the award of the Distinguished Service Cross, he has destroyed several other enemy aircraft and has shown great dash and enterprise in attacking enemy troops from low altitudes despite heavy anti-aircraft fire.’

At the time of the Armistice, Camels were in service with many front line RAF squadrons in France. As well as with UK Home Defence squadrons, they also served in Italy, Greece and Russia. The type also equipped some United States Air Service squadrons in France. Around 1300 enemy aircraft were downed by pilots flying Camels. Its continued use in the post-war RAF was limited by the arrival of the Sopwith Snipe, though it did continue to fly with the air arms of other countries well into the 1920s.

Exact reproduction

Of the more than 5500 built, few original Sopwith Camels survive today. The Vintage Aviator Ltd’s flying reproduction ‘B3889’, as illustrated within these pages, may not be an original airframe but is as close as can be to seeing the real thing fly – especially as it is powered by an original Gnome rotary engine.

This wonderful aeroplane wears the colours of New Zealander Captain Clive Collett, who was the first pilot to score a victory with the Sopwith Camel. He eventually scored 12 confirmed ‘kills’, but died in a crash while test flying a captured Albatros during 1917.

This aircraft made its debut at the 2001 Classic Fighters airshow held at Omaka, Blenheim, Marlborough, on New Zealand’s South Island. This was particularly appropriate, as Clive Collett originated from Marlborough. It has gone on to appear at many further airshows including subsequent biennial Classic Fighters and at its home at Hood Aerodrome, Masterton, on New Zealand’s North Island. As well as its engine, the Camel features some other original components too, adding to its authenticity.

The Camel was held in such high regard by those who flew it during World War One, that it has often been likened to having the iconic status gained by the Spitfire in World War Two. With its impressive combat record, it later gained a more glamorous nickname than its first – ‘King of the Air Fighters’.

Sopwith works

The Sopwith Snipe was designed to replace the company’s superb Camel. This photograph showing the production of Snipes was taken at the Sopwith works at Ham on 12 September 1918. A ferocious German offensive that opened in the spring of that year stretched the newly formed RAF to its limits trying to keep the front-line fighter squadrons up to strength, so it wasn’t an ideal time to introduce a new type into widespread service. The first unit to receive the Snipe was 43 Squadron in August, followed by 201 Squadron in October. The only other unit to enter combat with the Snipe during World War One was 4 Squadron Australian Flying Corps. Major WG Barker VC DSO* MC*, flying a Snipe, single-handedly engaged large formations Fokker D.VIIs on 27 October 1918 for which he was awarded his Victoria Cross. The citation in the London Gazette of 30 November 1918 tells the story: ‘On the morning of the 27 October 1918, this officer observed an enemy two-seater over the Foret de Mormal. He attacked this machine and after a short burst it broke up in the air. At the same time a Fokker biplane attacked him, and he was wounded in the right thigh, but managed, despite this, to shoot down the enemy aeroplane in flames. He then found himself in the middle of a large formation of Fokkers who attacked him from all directions, and was again severely wounded in the left thigh, but succeeded in driving down two of the enemy in a spin. He lost consciousness after that, and his machine fell out of control. On recovery, he found himself being again attacked heavily by a large formation, and singling out one machine he deliberately charged and drove it down in flames. During this fight his left elbow was shattered and he again fainted, and on regaining consciousness he found himself still being attacked, but notwithstanding that he was now severely wounded in both legs and his left arm shattered, he dived on the nearest machine and shot it down in flames. Being greatly exhausted, he dived out of the fight to regain our lines, but was met by another formation, which attacked and endeavoured to cut him off, but after a hard fight he succeeded in breaking up this formation and reached our lines, where he crashed on landing. This combat, in which Major Barker destroyed four enemy machines (three of them in flames), brought his total successes to fifty enemy machines destroyed, and is a notable example of the exceptional bravery and disregard of danger which this very gallant officer has always displayed throughout his distinguished career.’

Late production Snipes at the Ham factory in December 1918. Soon after the Armistice large numbers of newly built Snipes were scrapped, but three years later it was realised this decision had been made in haste and in 1921 the scrapping was stopped. A programme of salvage and rebuilding then took place and more than 200 Snipes were returned to service. Powered by a Bentley BR 2 engine, the Snipe was capable of more than 120mph and remained in RAF service until 1926.

Video

Video

Albatros D.Va reproduction World War One aircraft. In 1916 most German aircraft manufacturers were directed to look at what made the Allied Nieuport fighters so effective, and to incorporate those elements into their new aircraft designs.

Albatros redesigned their D.II model as a sesquiplane, like the Nieuports, with a lower wing with a narrower chord width than the upper wing. The resulting D.III was a great new aircraft and established itself as a formidable fighter throughout 1917.

In mid-1917 the D.V/Va was an attempt to improve on the D.III to keep up with newly deployed Allied aircraft such as the R.A.F. S.E.5a and Sopwith Camel. The D.Va was strengthened and had a streamlined oval fuselage instead of the flat sided one of the D.III. However, these and other minor changes were not enough to keep the D.Va at the forefront of fighter technology.

By early 1918 the D.III and D.Va were being replaced at the front by new Fokker Dr.1s and then D.VIIs. Despite this the aircraft remained in active service through until the Armistice in November 1918.

This aircraft is an authentic reproduction built by The Vintage Aviator Ltd (TVAL) in New Zealand — http://www.thevintageaviator.com. The flying sequence shown here was part of the aircraft’s display routine at the TVAL flying day held at Hood Aerodrome (Masterton, NZ) in April 2010.