It was with some humility that I chose the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain as the subject for this issue of Aviation Classics. As I witnessed several occasions marking the event, it struck me how much widespread national respect there still is for those who fought that crucial aerial battle.

It was with some humility that I chose the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain as the subject for this issue of Aviation Classics. As I witnessed several occasions marking the event, it struck me how much widespread national respect there still is for those who fought that crucial aerial battle.

But alas, as highlighted within these pages in the interview with ‘Stapme’ Stapleton, ‘The Few’ are getting ever fewer. I was saddened to think of how ‘Stapme’ would have been so keenly involved with this year’s commemorations, so I tried hard to ensure that the precious time I was privileged to spend with the veterans, now mostly in their 90s, had a strong input to this publication.

The first time I met a veteran of the Battle is still strong in my memory. I was an Air Cadet at the time, and on summer camp at RAF Manston in Kent – itself a famous Battle of Britain airfield. The Manston Spitfire Memorial Building had only recently been opened, and we were most excited to be shown around the fighter by Robert Stanford Tuck. It made my will to join the Royal Air Force ever stronger.

At the time of the Battle’s 50th anniversary in 1990, I was serving overseas at Brüggen with the RAF Germany Tornado force. I felt slightly envious of those lucky enough to be on parade for the occasion outside Buckingham Palace on 15 September, but our job had just taken a serious turn. Following the invasion of Kuwait by Iraqi forces, the first jets from Brüggen had left for the Gulf on 27 August. After many years dominated by Cold War operations in Europe, suddenly Tornados were departing to a desert environment unfamiliar to the personnel of the time. So on the brink of that important anniversary the RAF was taking on a new challenge, though as stated by Geoffrey Wellum on page 129 the ethos and Esprit de Corps of the Service hasn’t changed – and when the Gulf War later began it again fought with distinction.

I sincerely hope that this edition of Aviation Classics, first published to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, highlights the debt we owe to ‘The Few’.

I sincerely hope that this edition of Aviation Classics, first published to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, highlights the debt we owe to ‘The Few’.

Jarrod Cotter

Editor

Contents

Contents

6 Introduction – The debt we owe

8 The letter that changed the course of history

10 The Battle of Britain

22 Spitfire or Hurricane – which was the best fighter in the Battle of Britain?

28 Spitfire versus Bf 109

From a technical viewpoint

30 RAF Bentley Priory

HQ Fighter Command

34 Kent’s place of pilgrimage

38 London’s monument

40 Battle Honour

Battle of Briatin 1940

42 Making an epic

46 Corpo Aereo Italiano

48 “Like a pea falling on a tin plate”

52 Battle of Britain spirit flies on in the RAF

56 The Battle on canvas

58 They also served

66 RAF Duxford

Battle of Britain fighter station

72 Fighter VC

74 Telling the story of the Battle

78 Taming the ‘Sea Lion’

84 Biggin Hill’s RAF Chapel

of Rememberance

88 Across the Channel

92 Messerschmitt Bf 109E cockpit

94 ‘Defender of London’ 1940

98 Hurricane scramble

100 Combat Hurricane

102 Paying the price of freedom

108 ‘Emil’

110 Battle of Britain Day

112 Spitfire ‘Ditching’

114 Bader’s Battle

116 ‘Stapme’ Stapleton

One of ‘The Few’

120 Rare opportunities

122 Tribut to ‘The Few’

Spitfire or Hurricane

A special preview feature from Aviation Classics – Which was the best fighter in the Battle of Britain? Squadron Leader Clive Rowley MBE RAF Ret’d uses his first-hand experience as an RAF fighter pilot and former Officer Commanding Battle of Britain Memorial Flight to argue a debate that has gone on for 70 years!

A special preview feature from Aviation Classics – Which was the best fighter in the Battle of Britain? Squadron Leader Clive Rowley MBE RAF Ret’d uses his first-hand experience as an RAF fighter pilot and former Officer Commanding Battle of Britain Memorial Flight to argue a debate that has gone on for 70 years!

I am, or to be more precise was, a fighter pilot. I say “I am” because after 26 years in that capacity you cannot easily change your mindset. Fighter pilots live, work, fly, fight, and sometimes die, in an extremely competitive environment. Winning or losing may well mean the difference between life and death in the fast-moving and lethal regime of aerial combat. Fighter pilots want, indeed need for sheer survival, to be the best – and they want to be flying the best.

There are three tangibles that may affect the outcome of aerial combat. To win you need superior equipment, tactics or training/experience, or a mixture of those factors. Beyond that, there are only the intangibles that may affect the result; things such as fighting spirit, aggression, courage and luck, which should not, perhaps, be relied upon for guaranteed victory.

If my time as an RAF fighter pilot had started 33 years earlier than it did, I would have been flying and fighting in the Battle of Britain. In order to have given myself the best chance of winning and surviving, which of the main two RAF fighter aircraft would I have preferred to have flown – the Hurricane or the Spitfire? Which would you prefer if it was you?

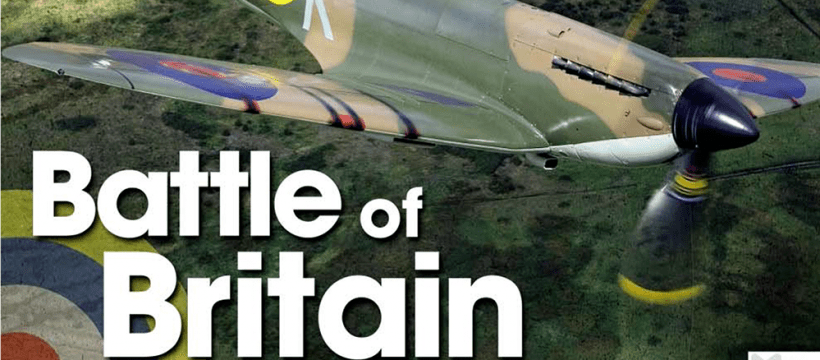

In addressing that question, I call not only on my background as a ‘modern’ professional fighter pilot, but also on the privileged time I spent flying both of the contenders during my 11 years flying with the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (BBMF). Of course, I did not have to fight a war in them; I flew these ‘warbirds’ only for display purposes and in benign conditions. But I flew Hurricanes very similar to those flown during the Battle of Britain and I flew many hours on the BBMF’s Spitfire IIa P7350, the only surviving, airworthy example of its type that actually flew and fought in the greatest air battle of all time.

Context

Which is the better Battle of Britain fighter, the Supermarine Spitfire or the Hawker Hurricane? It is a perennial question, which has been debated among pilots, historians and enthusiasts since 1940, and it is a question to which there is no definitive answer. Each aircraft had its strong and weak points and each of us probably has our own favourite – I know I do. The question needs a context. Best at what? Against what?

At the time of the Battle of Britain, the British fighter pilots had no doubts whatsoever about their ability to take on the Luftwaffe bombers, which their Hurricanes and Spitfires could out-perform in every department. That said, RAF fighters were brought down and pilots were killed by return fire from the German bombers, so it was still a dangerous occupation.

The Luftwaffe single-engine fighter that the RAF pilots faced, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, was a different proposition though; it was a much more dangerous opponent. Indeed, the Bf 109 accounted for most of the losses suffered by Fighter Command during the Battle. So the real context of the question is, which of the two RAF fighters compared most favourably with the Bf 109, as well as which was ‘the best’ in terms of the overall victory in the Battle.

The first thing to note is that the RAF fighter pilots at the time of the Battle of Britain did not have any choice over whether they flew Hurricanes or Spitfires. Military organisations are not democracies and the pilots had to go where they were sent and fly what they were told to fly. The RAF fighter pilots of 1940 were undoubtedly proud to fly either type. Both aircraft were considered as modern pieces of equipment at the time, both were pushing the boundaries of performance beyond anything that humans had experienced before. After all, for most normal people at the time, the fastest thing that they had travelled in was a train!

Design and construction

When the Battle of Britain commenced, RAF Fighter Command fielded 30 squadrons equipped with Hurricanes and 19 squadrons with Spitfires. On the evening of 14 September, prior to the defining day of the Battle, there were a total of 533 Hurricanes and 269 Spitfires serviceable and available to fight – almost twice as many Hurricanes as Spitfires. So it was twice as likely that a Battle of Britain fighter pilot would go into combat in a Hurricane rather than a Spitfire.

From a strategic point of view, therefore, the Hurricane wins the contest simply because there were almost twice as many of them available to fight during the Battle and it, therefore, played the greater part.

This was no mere accident. Neither was it due only to the fact that the Hurricane entered squadron service eight months ahead of the Spitfire. Sir Sydney Camm’s design for the Hurricane followed that of the earlier Hawker biplanes but without the top wing. The rear fuselage from the pilot’s seat rearwards was built as a framework of metal longerons, struts and tie-rods with wooden formers and stringers, covered in doped fabric (Irish linen). Designed to use as many as possible of the jigs, tools and skills available at Hawkers, it was a halfway house between the old biplanes and the newer stressed skin designs of the Spitfire and the German Bf 109.

Hawker’s use of the old technology ensured that as many Hurricanes as possible could be built rapidly for the war effort. The Air Ministry calculated that building a Spitfire took 15,200 man-hours but a Hurricane took only 10,300. There were other advantages to the construction of the Hurricane. Exploding cannon shells that did terrible damage to metal skin had less effect upon the Hurricane’s tubular metal framework and fabric skin. In addition, early on in the war, the RAF had very few men who understood the complexities of stressed metal construction, but its airframe fitters had spent their lives servicing and rigging aircraft built like the Hurricane and so could keep them serviceable and flying more easily. Many seriously damaged Hurricanes were repaired in squadron workshops while heavily damaged Spitfires were often pulled out of the front line and sent away to maintenance units for repair or were simply written-off.

From the point of view of the pilot in the cockpit, trying to shoot down enemy aircraft while also staying alive, there are several factors which may make one fighter aircraft better than another; among these are: aircraft performance, the visibility from the cockpit, the armament and ease with which the guns could be brought to bear, and survivability.

Power and weight

Engine power and the aircraft’s power-to-weight ratio are obvious factors that will affect performance. The Hurricane Mk.I and Spitfire Mk.Ia in service at the time of the Battle of Britain shared the same Rolls-Royce Merlin III engine, driving a three-bladed constant-speed propeller and producing the same amount of power (a nominal 1030hp). Their main opponent, the Bf 109, was fitted with a Daimler-Benz engine, which produced a roughly comparable 1150hp. The Hurricane was the heaviest of the three aircraft (the Bf 109 being the lightest) so it had the worst power to weight ratio. This, coupled with the fact that its airframe and thick wing section produced considerably more aerodynamic drag than either the Spitfire or Bf 109, meant that the Hurricane had the least impressive climb and speed performance figures. The Bf 109 possessed the best power-to-weight ratio of all three fighters and this was reflected in aspects of its impressive ‘top-end’ performance.

Rate of climb

Climb rate was an aspect that particularly concerned the RAF fighter pilots during the Battle of Britain. The Hurricanes and Spitfires were almost invariably scrambled to intercept incoming raids, often later than the pilots would have wished. The time taken to climb to height therefore became tactically critical if the RAF pilots were to stand any chance of engaging the enemy formations with an altitude advantage, which in fact they rarely achieved. The Spitfire had a clear performance benefit over the Hurricane in its time to height, taking a minute less to reach 20,000ft. The Bf 109 had a rate of climb superior to both the RAF fighters but this was less of a factor to the Germans during the Battle of Britain as they had plenty of time and distance to achieve their desired height before they were engaged. The Bf 109’s excellent climb rate could, however, be used to good effect by experienced Luftwaffe pilots during combats, especially if they started off with a height and, therefore, an energy advantage so that diving attacks could be followed by a zoom climb.

Incidentally, the Spitfire’s climb rate advantage over the Hurricane was apparent with the BBMF aircraft that I flew. On air tests, a timed climb to 7000ft was conducted and I would expect the Spitfire to be one minute quicker in the climb than the Hurricane.

Speed

The Hurricane also lost out to the Spitfire and to the Bf 109 in terms of maximum level speed by some margin. Due to the extra drag created by its airframe and thick wing section, and its slightly inferior power-to-weight ratio, the Hurricane could typically manage about 325mph in level flight, some 25mph below the maximum level speed for the Spitfire and the Bf 109. This could be significant, as it could seriously compromise the Hurricane’s ability to close on a fast-moving opponent or, perhaps even more important, to get away from one.

Roll rate

Many of the Battle of Britain dogfights between Bf 109s and the British fighters started with the 109s bouncing the RAF fighters from above. As long as the RAF fighter pilots saw them coming – and that is a big ‘if’ – they could roll into a 90 degree banked break-turn and pull hard into the enemy attack. This would almost invariably cause an overshoot by the Bf 109, the pilot of which would be unable to turn with either a Spitfire or a Hurricane. The ability to roll rapidly into such a break turn was therefore vital and the Spitfire had a roll rate advantage over the Hurricane (which was further improved when metal ailerons were fitted to the Spitfire), although the Bf 109 rolled quicker than either of them. All three types suffered from reduced roll rates at high speed when the ailerons became very heavy, but the Spitfire with metal ailerons suffered less from this than the other two types.

Turning

Once into the break turn, the comparative rates and radii of turn became the important factors. The wing loadings of the Hurricane and Spitfire were almost identical. The Bf 109’s was considerably higher. Wing loading is an important factor in how much lift the wing can produce and therefore how much of that can be translated into a turning vector in a steeply banked turn (the lower the wing loading, the better). The Hurricane actually possessed an advantage over the Spitfire in its turning ability, with a fractionally greater turn rate (in degrees per second) and a significantly lower turn radius once the turn had become established and sustained. Both the Spitfire and the Hurricane had a better turn rate and smaller turn radius than the Bf 109 and if well flown, could fare very well in a dogfight with the German fighter. The Hurricane, though, would tend to bleed energy in a hard turn more easily than the Spitfire. This resulted from the lower power-to-weight ratio of the Hurricane compared with the Spitfire and from the higher lift-induced drag that the Hurricane wing produced.

These factors were apparent to me when I flew the BBMF display sequence in both types. With the same power set, the Hurricane would be more inclined to lose speed (‘energy’) if it was hauled around the sky too tightly, while the Spitfire retained speed in the same manoeuvres. In a prolonged turning combat, the Hurricane pilot would therefore be more likely to find himself relying on his minimum radius of turn rather than having sufficient energy to achieve a higher rate of turn. This would make the Hurricane pilot more defensive and less offensively capable.

The superior turning capabilities of the British fighters meant that Bf 109 pilots were best advised not to get into a turning fight with either the Hurricane or the Spitfire. Their best option was to use ‘hit and run’ tactics, diving down with superior energy, hoping to attack unseen, then if spotted and if an attack was spoiled by the British fighter’s break turn, to disengage, zoom back up or continue on down and away with the extra starting speed. Such tactics were very effective in the early stages of the Battle when the German fighters roamed ahead and above their bombers as a fighter sweep. When the German fighter pilots were ordered to provide their bombers with close escort, their tactical freedom was curtailed and they were less able to utilise the strengths of their own aircraft and instead played into the hands of the British. In these regimes there is no clear winner between the Hurricane and the Spitfire.

Stability versus agility

The Hurricane’s stability is famed and is usually mentioned in commending the aircraft as a steady gun platform. However, stability and agility are effective opposites in terms of aircraft design and handling. The Hurricane was, indeed is, if my personal experience is anything to go by, a very stable aircraft. If the pilot does not make any control inputs to alter the status quo, the Hurricane is as steady as a rock. However, if the Hurricane pilot wants to manoeuvre his aircraft rapidly in a dynamic environment such as aerial combat, this takes more doing. With the two examples of the Hurricane that I was privileged to fly, which I can only assume are typical, I found that it took a large control input to get the aircraft moving, especially in pitch – a small movement of the control column from the neutral point wouldn’t budge it, almost as if there was something of a dead area. Then having got it moving, it was necessary to back off the input so as not to overdo it. I always found this slightly strange compared with all the other aircraft I had flown. In addition, the controls could hardly be called ‘well harmonised’ as they were weighted differently in roll and pitch.

The Spitfire, on the other hand, is neutrally stable about all axes, the control forces are light even at high speeds (excepting the limitations of the early fabric-covered ailerons on roll control at high speeds), the controls are sensitive and well harmonised and the aircraft is extremely responsive. The Spitfire will maintain a flying attitude with hands and feet off but the pilot can move it quickly and effortlessly into any manoeuvre he desires. This is what makes the Spitfire such a delight to fly – virtual finger-tip control throughout the flight regime – and the reason why anyone who has flown one loves the feel of it and everyone who has read about it wants to experience it.

These differences in the control responses between the Hurricane and the Spitfire will in truth have little bearing on either aircraft’s ability or performance in combat, but the Spitfire pilot may well feel more in control of his mount and better able to manoeuvre rapidly, which is a nice feeling. To counter that though, I have had some wartime veteran pilots tell me that they felt they were too ‘ham-fisted’ for the Spitfire and actually preferred the feeling that the Hurricane needed to be ‘hauled around the sky’. I think they were being over-modest as, if anything, the Hurricane is actually more difficult to fly well than the Spitfire.

Stalling

The stalling characteristics of the Hurricane and the Spitfire differ markedly and this could affect the confidence that pilots had in flying their aircraft to the limits and, therefore, in generating the maximum possible turning performance. The Spitfire’s beautiful elliptical wingtips are as near to an optimum aerodynamic design as you can get for the speed regime in which it operated. The elliptical wing shape generates the least lift-induced drag by minimising the wing tip vortices. This is one of the principal reasons why the Spitfire generates less drag than the Hurricane when turning hard. Also, when the wing roots of the Spitfire have stalled, the wingtips will still be flying quite happily, and the ailerons provide good roll control even at the stall.

A stall in the Spitfire is characterised by some buffet being transmitted though the control column from the elevators, giving ample warning, then at the stall a loss of lift and a ‘mushing’ sensation in a turn, but with no tendency to drop a wing or to flick. The stall in a Spitfire, even in a hard turn, is completely benign and the aircraft can easily be flown to its limit and at its optimum angle of attack with great confidence. In the air the Spitfire was, and is, totally forgiving of any over-enthusiasm by the pilot. The Hurricane on the other hand gives its pilot less warning of the approaching stall and will invariably drop a wing if fully stalled. In a hard turn this might lead to the Hurricane ‘flicking’ if pulled too hard into the turn. The Spitfire is much the nicer of the two aircraft in this respect.

Cockpit visibility

The visibility from the cockpit is obviously of great importance to the fighter pilot if he is to stand any chance of seeing enemy fighters attempting to ‘bounce’ him before they kill him. The pilot’s view from the Spitfire, and again I speak with the privileged benefit of personal experience, is excellent to the side and rear. The ‘blown’ bubble-shaped canopy-hood allows the Spitfire pilot to see right round behind the aircraft; with the seat harness shoulder straps loosened slightly (the way I always flew, except for take-off or landing) it is possible to twist around so that you can actually see the fin and, more importantly, any other aircraft coming from that direction. The view through the Hurricane’s ‘lattice-work’ canopy is naturally more restricted, and the view to the rear is nowhere near as good as the Spitfire, as the flat sides of the hood stop the pilot from getting his head far enough over and around.

In both aircraft, I personally found the rear-view mirrors to be of limited value, as an attacking aircraft would still be a speck in the mirror when it was at open-fire range – better than nothing though. The one area where the Hurricane has a slight advantage in terms of visibility is over the nose. The Hurricane’s slightly sloping nose gives a better view ahead than that over the long straight nose of the Spitfire; and this would allow a Hurricane pilot to pull more lead when taking a deflection shot without losing the intended target under the nose. The Bf 109 pilot, also looking through a ‘lattice-work’ canopy, had similar problems to the Hurricane pilot.

Armament and gunnery

During the Battle of Britain, the Hurricane and the Spitfire shared identical armament in the form of eight 0.303 Browning machine guns. (The initially unsuccessful experiments with 20mm cannons on the Spitfire were not to benefit the RAF fighter pilots until after the Battle). The pilots of both RAF fighters had a similar amount of firing time (16 seconds in a Spitfire, 17 seconds in a Hurricane). The Bf 109E was equipped with cannons as well as machine guns and this armament could make its firepower quite devastating against the British fighters. The weight of fire from a three-second burst of gunfire from the Hurricane or Spitfire was 10lb, while for the Bf 109, with cannons and machine guns, it was 18lb.

Every pilot who flew the Hurricane said it was an excellent gun platform, not least because of its rock-steady aircraft stability. In addition, the Hurricane’s sturdy wings provided solid bracing for the guns which were mounted in twin batteries of four, closely grouped together in each wing, as close in to the fuselage as they could be placed to clear the propeller. Because of its thin wing, the Spitfire’s armament of machine guns had to be spread out along the wing, with the outboard gun a third of the way in from the wingtip, then a group of two and then an inboard gun on each side. The wings would flex in turbulence or when pulling G and so the guns could be slightly out of line from their ground harmonisation when they were fired, making them less accurate especially over range. Although there is no difference in the armament between the Battle of Britain Hurricanes and Spitfires, the Hurricane was clearly the better gun platform.

Survivability

Armour plating provided the pilots of all three types of aircraft with similar levels of protection (by the time of the Battle of Britain). The Hurricane, with its rugged construction, could absorb an enormous amount of punishment and still get the pilot home safely. This was not so true of the rather more delicate Spitfire.

All three of the single-engine fighters, from both sides, suffered from weak or critical points which if hit by enemy gunfire, would bring powered flight to a rapid and premature end. Principal among these were the radiators and cooling systems, which were easily damaged and without which the liquid-cooled engines would not run for long. Of most concern to the pilots was the possibility of fire and, as we know, many of them were terribly burned before they could get out of their cockpits. The fuel tanks in the Spitfire were in the nose, ahead of the pilot and behind the engine. The Hurricane had a fuel tank in each wing and the so-called ‘Reserve’ fuel tank (rather a misnomer) in the nose ahead of the pilot and above his feet on the rudder pedals. These fuel tanks were supposedly ‘self sealing’, but this system did not work against cannon shells which would cause too great a rupture and an almost immediate fire, which could easily spread into the cockpit, especially in the case of the Hurricane.

When the pilots opened the cockpit canopy to bale out, this drew the flames further into the cockpit like a blowtorch. Neither the Spitfire nor the Hurricane was immune from this possibility and there was not much to choose between them in these terms, although the positioning of the Hurricane’s tank above the pilot’s feet was perhaps the least desirable. There is no indication that baling out of either aircraft was more difficult, or less likely to be successful, than the other.

One important aspect of survivability was landing! The Hurricane had a distinct advantage over both the Spitfire and the Bf 109 because of the relative ease with which it could be landed. The view over the nose of the Hurricane makes it easier to see ahead on the approach to land. The wide, sturdy undercarriage (coupled with effective rudder control when the tail is down) gives much better directional stability and control on the ground. The Hurricane was far better suited to rough landing strips and landings in less than ideal circumstances. With the Spitfire, on the other hand, the narrow-track undercarriage does not assist the aircraft to ‘tramline’ on the ground, and the relatively small fin and rudder do not endow it with great directional control, especially once the tail wheel is down on the ground and the nose and fuselage are blanking the tail. Where the Spitfire is forgiving of its pilot in the air, the Hurricane is the more forgiving of any mistakes by its pilot on landing. (The Bf 109 rightly had a notorious reputation for landing accidents and some 10 per cent of the losses of Bf 109s occurred on landing.)

Hurricane or Spitfire?

The question of which is the best Battle of Britain fighter – Hurricane or Spitfire – does not have a definitive answer. Each aircraft had its advantages and its disadvantages. Each was created under a completely different set of circumstances and came from totally different backgrounds and antecedents; they could not, in fact, have been more different from one another. What is clear is that, within the context of the Battle of Britain, and using the ‘yardstick’ of the Bf 109 as the most capable opponent they had to face, the advantages and disadvantages of each were not particularly significant and tended to balance each other out. Both aircraft were equally capable fighters in the combat environment they faced during the Battle, and they both played a decisive and equally vital role in the eventual victory.

Statistics from modern research show that the 19 Spitfire squadrons operating during the Battle of Britain are credited with 521 victories (an average of just over 27 per squadron) and a victory-to-loss ratio of 1.8:1. In comparison, the 30 fully engaged Hurricane squadrons are credited with 655 victories (an average of just fewer than 22 per squadron) and victory-to-loss ratio of 1.34:1. On the basis of the statistics alone, therefore, perhaps the Spitfire has a slight edge. We know that it was the Spitfire that the German Bf 109 fighter pilots feared the most; they felt that they should not fall victim to a Hurricane’s guns, although, of course, many did.

From a purely personal point of view, if my time as an RAF fighter pilot had started during the Battle of Britain, I would, I am sure, have felt quite confident going into combat in a Hurricane. That said, with the benefit of the experience of flying both, I would choose the Spitfire if I had the choice. As one Battle of Britain veteran said to me when I asked him the question a few years ago: “The Hurricane was all right until you flew a Spitfire!” There were, however, a number of fighter pilots during the Battle who flew Spitfires first and then transitioned on promotion to Hurricanes, invariably without complaint.

Conclusion

More telling than attempting to differentiate between the advantages and disadvantages of the Hurricane and the Spitfire is the conclusion that the RAF fighter pilots did not have vastly superior equipment to the opposition during the Battle of Britain. I have suggested that there are three tangibles that could affect the outcome of aerial combat: superior equipment, tactics and training/experience. Not only was there not a significant advantage in equipment, but also neither was there in the other two factors. British tactics were poor when the Battle began although they steadily improved. The initial tight formations flown by Fighter Command, with elements of three aircraft in a ‘Vic’, were a hangover from peacetime training and meant that most of the pilots in the formation were concentrating on station-keeping rather than looking out to avoid being bounced.

The Germans, meanwhile, started well with their more flexible and manoeuvrable tactical formations and by working to the strengths of their Bf 109s by sweeping ahead and above the bombers. They lost their tactical advantage when they were tied to providing close escorts to the bombers.

The pilots on both sides were trained to similar standards. Even those young RAF fighter pilots who were famously thrown into battle with very few flying hours on Spitfires or Hurricanes had typically received over 150 hours of previous flying training of a high standard. The RAF fighter pilots were in many cases short of combat experience compared with the Luftwaffe pilots, but if they lived through the first few fights, this was quickly rectified.

So, if there was no particular advantage to the RAF pilots over the Germans in equipment, tactics or training/experience, how did victory in the Battle of Britain come the way of the British? It leaves only the conclusion that the real key to the victory lay in the RAF pilots themselves. Their character and determination, their aggression, courage and sheer fighting spirit, aspects which I earlier suggested ought perhaps not to be relied upon for guaranteed victory, were in fact the deciding factor. It really was a close run thing!

Corpo Aereo Italiano

Corpo Aereo Italiano

A special preview feature from Aviation Classics – Luigino Caliaro highlights the participation of the Italian Regia Aeronautica during the late stages of the Battle of Britain.

A special preview feature from Aviation Classics – Luigino Caliaro highlights the participation of the Italian Regia Aeronautica during the late stages of the Battle of Britain.

The participation of the Regia Aeronautica in the Battle of Britain may be considered a purely political, instead of military, decision. At the closing of the hostilities with France in the summer of 1940, Mussolini decided to create an Expeditionary Corps to support the Luftwaffe on raids across Channel, thus giving the Italian armed forces a representation in the Battle of Britain.

Consequently on 10 September 1940 the Corpo Aereo Italiano (CAI) was formed, comprising bomber and fighter units that were based in Belgium. General SA Rino Corso Fougier was selected to command the CAI. Personnel amounted to 89 officer and 69 NCO pilots, 81 mechanics and 171 other personnel with diverse tasks.

Considering the technical characteristics of the Italian aircraft, especially the fighters which once over England had only 10 minutes loitering capability, a special operations area was arranged with the German command, reserved for the Italian aircraft. This area was limited by the 53rd parallel to the north, the 1°W meridian to the west and the Thames to the south. Logistics were established to make the units operational: the Germans would furnish installations and equipment to be managed by the Italians. German efficiency, as usual, was remarkable – Italian personnel arriving on the Belgian bases found good installations complete with camouflaged dispersal areas. All other logistic material was dispatched from Italy by train or transport aircraft, the whole transfer being completed by 24 September.

Very soon the deficiencies of the Italian equipment became evident. The aircraft lacked any sort of armour and the crews were not used to the demanding weather conditions over the Channel, which sometimes rendered operations extremely difficult. These deficiencies were compounded by the lack of navigation and radio communication equipment and the language difference with the Germans.

On the night of 24 October a formation of Fiat BR20Ms went out on their first bombing mission attacking the port installations of Harwich and Felixstowe in unfavorable weather. Twelve bombers from 13° Stormo and four from 43° Stormo were detailed for this mission, which began in the worse manner when MM21928 of 5° Squadriglia crashed just after take off fromMelsbroeck killing its whole crew. Two other bombers turned back due to mechanical failures and the remaining aircraft managed to drop their load of 100kg bombs on the target despite intense anti-aircraft fire that damaged one machine. The return flight was heavily hampered by the adverse weather resulting in the loss of MM21895 and MM22601 which, following radio failures, both got lost forcing their crews to bale out.

After this first mission it was decided to operate on day bombing missions only, such as the attack on the port installations at Ramsgate on 29 October by 15 bombers of 43° Stormo escorted by fighters of 56° Stormo. Two aircraft turned back with mechanical failures and the remainder dropped 72 100kg and nine 250kg bombs on the target. The flak was particularly heavy and several of the Italian aircraft were hit, one of which failed to return with its crew baling out over Belgium.

The next mission was on 1 November, the day after the Battle had officially ended. Sporadic sorties continued until 23 December 1940, when the order came for the remaining CAI aircraft still in Belgium to return to Italy by January. The last bombing mission was carried out by four BR20Ms of 13° Stormo attacking the port of Harwich on 2 January. Personnel losses amounted to 34 killed and 22 wounded, of which 14 were killed and nine wounded in aerial combat.

Though most of the CAI returned home, two Fiat G50 units from 20° Gruppo remained in Belgium operating in an autonomous way under control of the Luftwaffe until April 1941, engaged in patrols and interception duties. It was initially considered to re-equip the Italians with Bf 109Fs, but after an initial training period it was decided to send those remaining back to Italy too.

The whole operational activity in the three months that the CAI was based in Belgium amounted to 144 bombing sorties, 1640 fighter sorties and five reconnaissance missions. Losses amounted to 11 bombers and 25 fighters, of which 26 were due to accidents or mechanical failure. It is remarkable that the Fiat G50 monoplane, while of a more modern design than the Fiat CR42, was engaged in the operations in a very limited way, mainly due to its short range. Therefore, very often the BR20 escort duties fell to the CR42 biplanes.