With Peter Jackson’s new ‘take’ on the ‘dam busters’ legend currently in production, Jonathan Falconer looks back to the original – and some might say never-to-be-bettered The Dam Busters – when real RAF bomber pilots flew real Lancasters on camera.

For many cinemagoers, The Dam Busters is probably the best-known and loved British war film of the post-World War Two era. Based on Wg Cdr Guy Gibson’s own account in Enemy Coast Ahead, and Paul Brickhill’s best-seller The Dam Busters, Michael Anderson’s 1955 docu-drama recreates the tension and bravery of 617 Squadron’s audacious raid on Nazi Germany’s Ruhr dams in May 1943. The result is among the finest war films ever made.

For many cinemagoers, The Dam Busters is probably the best-known and loved British war film of the post-World War Two era. Based on Wg Cdr Guy Gibson’s own account in Enemy Coast Ahead, and Paul Brickhill’s best-seller The Dam Busters, Michael Anderson’s 1955 docu-drama recreates the tension and bravery of 617 Squadron’s audacious raid on Nazi Germany’s Ruhr dams in May 1943. The result is among the finest war films ever made.

When Associated British Picture Corporation bought the film rights to Paul Brickhill’s book in 1951, they needed pilots who could fly the Avro Lancaster on the film they planned to make. The Avro Lincoln shared many common features with the ‘Lanc’, so it was logical that its pilots would be the obvious choice to fly the Lancasters on camera.

Four operational Lincoln crews from 83 and 97 Squadrons at RAF Hemswell in Lincolnshire were picked to fly the Lancasters. Most of these men were fresh from a fourmonth detachment to Singapore flying air strikes against the Communist terrorists in Malaya. They were led by Flt Lt Ken Souter, a flight commander on 83 Squadron, who was ably supported by pilots FS Joe Kmiecik AFM (also from 83), and Fg Off Dick Lambert and FS Ted Szuwalski from 97 Squadron. Three flight engineers were picked to fly with the four pilots, since usually only three of the four Lancasters would be operating at any one time. They were FS Jock Cameron (of 83) and Sgts Mike Cawsey and Dennis Wheatley (of 97). In addition to the Lancaster flying, the crews continued to be involved in the regular squadron commitments, flying their Lincolns on Cold War exercises by day and night throughout the summer.

Ken Souter, who was chosen to lead the RAF aircrew for the film, had joined the RAFVR in 1939 and trained as a fighter pilot and later saw action in North Africa flying Hawker Hurricanes with 73 Squadron. Ken left the RAF in 1946 but rejoined in 1950. His first posting was to 83 Squadron on Lincolns. Joe Kmiecik was Polish and had flown Spitfires and Mustangs in action with 303 Squadron during World War Two. Like his fellow countryman, Ted Szuwalski, he had made a remarkable escape from a Soviet Gulag in 1941 and eventually made it to England where he joined the RAF. Dick Lambert joined the RAF in 1942, but due to everlasting delays in his flying training he missed the war by a matter of months. He was commissioned in 1950 and later joined 97 Squadron. Eric Quinney, from 83 Squadron, replaced Lambert when he was posted away from Hemswell late in the filming schedule during August.

For many, the stars of the film are undoubtedly the Lancasters themselves. It is hard to believe that Lancasters were in short supply when the filming commenced in April 1954. Four Mk.7 aircraft were taken out of storage from 20 Maintenance Unit at RAF Aston Down, Gloucestershire, and specially modified for the film. These were NX673, NX679, NX782 and RT686. In fact, ’673, ’679 and ’782 had already developed a taste for the movies because they had recently starred in Philip Leacock’s feature film about a wartime Lancaster squadron, Appointment in London, which was premiered in 1953. Other aircraft that had ‘walk-on’ roles in the film were Vickers Wellington T.10, MF628, and de Havilland Mosquito PR.35, VR803.

For Associated British it was an expensive business to lease the four Lancasters for filming. The Air Ministry charged the company £100 per engine hour running time, and as there were usually three Lancasters, the Varsity camera aircraft and/or the Wellington involved (3 x 4 engines and 2 x 2 engines), £1600 per hour in the early 1950s was no small sum. Today, this sum is equivalent to £1620 per engine hour, or £6480 per Lancaster per hour.

‘LANC’ MAKEOVERS

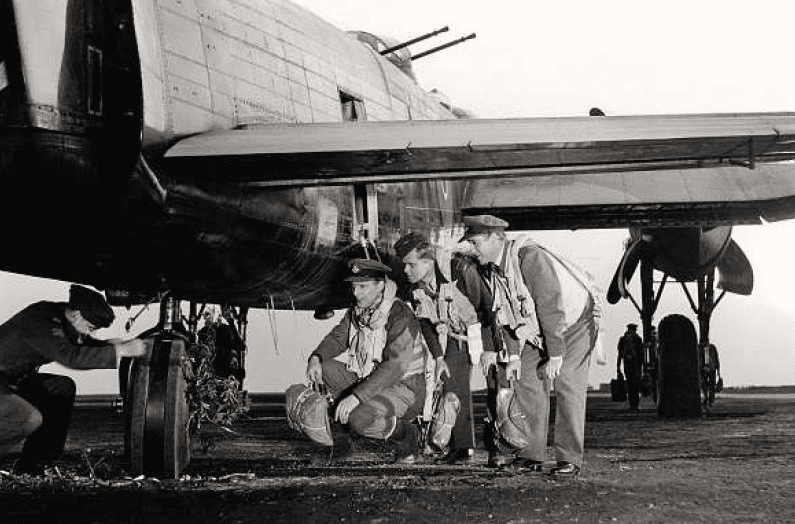

To make the Lancaster Mk.7s resemble as closely as possible the actual B.III (Type 464 Provisioning) aircraft that flew on the Dams raid in 1943, three (NX673, NX679 and RT686) were specially modified at Hemswell by a working party from the AV Roe Repair Organisation at Bracebridge Heath, Lincs. They had their mid-upper gun turrets (Glenn Martin Type 250 CE23), H2S radomes and bomb bay doors removed to convert them to the authentic ‘dam buster’ configuration. The bomb bay itself was further modified to create the rebated aperture from which the mock-up of the bouncing bomb was suspended.

However, the bomb itself was still on the secret list when the film was being made (it was only declassified in 1963), so the resulting mock-up bore little resemblance to the real thing. Made out of plywood and plaster of Paris, the slab-sided bouncing bomb mock-up for the film was somewhat larger in overall size than the real weapon, and deeper, which accentuated its shape and low-slung appearance for the benefit of the camera. The wooden replica was winched up into position in the bomb bay recess and secured to the aircraft by bolts. Being firmly attached to the Lancaster’s belly, the replica bomb was never intended to be dropped.

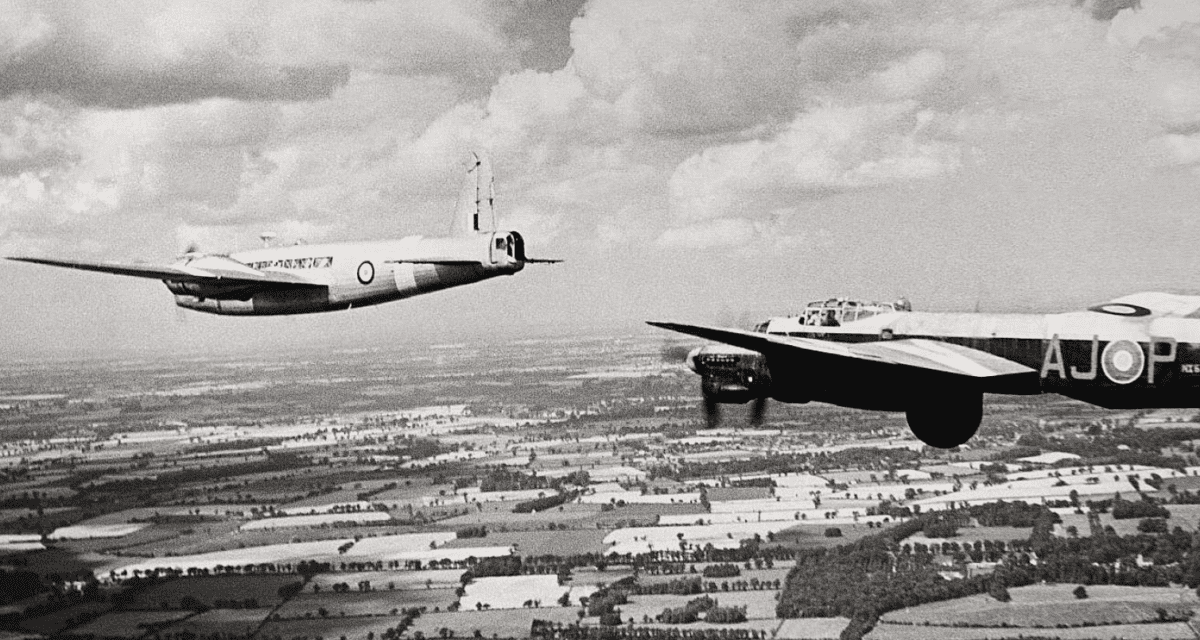

The upper surfaces of the aircraft and fuselage sides were then over-painted in the standard wartime European theatre night bomber camouflage of dark green and dark earth, with code letters in red, to cover the existing black and white paint scheme for RAF bombers serving in the Far East. The Flying for the cameras above the still waters of Lake Windermere. Mike Cawsey/Garbett & Goulding Collection undersides of the fuselage retained their night black scheme, although the under wing aircraft serial numbers were painted out.

Purists will notice a number of differences between wartime Lancasters and the Mk.7s that appear in the film. Perhaps the most obvious is the Frazer-Nash FN82 poweroperated rear turret that was equipped with twin Browning 0.50in machine guns. In 1943, the Lancasters of 617 Squadron would have been fitted with FN20 rear turrets armed with four of the less-potent 0.303in Brownings. In addition, the series of small windows along each side of the fuselage that were a noticeable feature of wartime Lancasters were deleted from the post-war Mk.7. And note, too, the absence of the engine exhaust covers that would have been present on wartime Lancasters to reduce glare and suppress sparks from the hot exhausts at night.

The film aircraft wore different squadron code letters on either side of the fuselage, thereby enabling three Lancasters to play the parts of six on screen. NX679 was painted to represent Guy Gibson’s ED932 AJ-G and it was the only aircraft to have its serial number altered for the film. The other Lancasters retained their correct RAF serials. NX673 was painted in the markings of Mick Martin’s P-Popsie (ED909 in 1943). One Lancaster, NX782, was retained as a standard Mk.7 and painted as ZN-G to represent Gibson’s aircraft when he commanded 106 Squadron, before being called upon to form 617 Squadron in March 1943. NX782 was the Lancaster that appears in the training flight flying sequences prior to Operation Chastise.

Although there was engineering support for the Lancasters at Hemswell and Scampton, when it came to the supply of spare parts it was necessary for an aircraft to be despatched north to 22 MU at RAF Silloth in Cumbria, which was engaged in breaking up Lancasters.

Under the overall control of the Director of Photography and Aerial Photography, Erwin Hillier, much of the superb aerial footage was filmed by Associated British’s second unit team led by the Special Effects Photographer, Gilbert Taylor, from a twin engined RAF Vickers Varsity, WJ920, on loan from the Bomber Command Bombing School, Lindholme, and flown by Flt Lt Scowan. Some of the air-to-air footage that required head-on shots of the Lancasters was taken from the rear turret of Wellington T.10, MF628, flown by Flt Lt ‘Butch’ Birch.

To facilitate filming, the metal floor of the Varsity was replaced by one made of wood, to which were attached camera tripods and grips. The aircraft’s nose section was also modified to take a forward-looking camera. A further two cameras were installed inside the aircraft, one beside the rear port side cargo access door and the other in the left-hand seat of the cockpit for which the cockpit window had been specially removed, the pilot flying from the right-hand seat. Mitchell and Arriflex cameras were used by Hillier and Taylor to film The Dam Busters.

FLYING AT 40FT

Most of the flying sequences were flown out of Hemswell during the week, and from Scampton at the weekends, with the aircraft returning to Hemswell at the end of each day’s filming. Each time the Lancasters flew it was for some sort of filming activity: takeoffs, formation flying, low flying and landings, but the greater part of their flying was done in formation.

Flt Lt Ken Souter recalled that as a team they didn’t really have any practice as such, but went more or less straight into the filming. Sgt Mike Cawsey, who was Ted Szuwalski’s flight engineer, recalls: “For our familiarisation we had a look at the Pilot’s Notes, examined the aircraft inside and out, ran the checks a couple of times and made sure we could start the engines.” In April the crews embarked on a programme of lowlevel flying.

Jim Fell clearly remembers the defining moments of his first training flight in a Lancaster: “I can clearly recall looking up at some gentlemen fishing at the end of Skegness Pier as we flashed past them. That morning, I learnt that if you got down low enough over water the propellers would whip up a spray.”

The weather across the British Isles in the months of June, July and August 1954 was far from ideal from the point of view of filming. Eric Quinney: “We flew most days ” if the weather was suitable and on quite a few when it was not. We would sometimes do two hours flying and get no productive filming due either to too much cloud, the wrong sort of light, or some other technicality. The director had no concept of how fatiguing it was flying these heavy aircraft and would expect us to fly a second sortie if the first was unsatisfactory.”

Gil Taylor remembers that the poor weather was a major hindrance for the second unit crew and did nothing to facilitate the aerial camera work: “It was the worst summer for years. The planes were full of petrol and so we just couldn’t sit and wait and hope for the weather to improve. We flew over the whole of southern England and up beyond Manchester to chase the clear weather. We simply couldn’t get the sun we needed, so on at least one occasion we literally chased the sun over to Holland – in fact to wherever we could get some exposure for matching weather. It was the biggest problem of all.”

Eric Quinney remembers that flying for the film was the most exciting time in his 20- odd years as an RAF pilot: “To be able to fly legally at a height of a mere 60 feet is exciting, but to do this in tight formation with some 30 tons of aircraft being controlled by one hand on the control column and one on the throttles really does get the adrenaline flowing. With three Lancasters in formation, each with a wingspan of over 100 feet, it is impressive but quite frightening when the lead aircraft starts to follow the prescribed route. One’s tendency is to edge away from the lead aircraft slightly as you feel he is going to slip down into you, but you can’t do that because in the banked turn you are much closer to the ground than 60 feet with your lower wingtip.”

On the real raid in 1943, the Lancasters of 617 Squadron were required to fly at a height of exactly 60ft over the Ruhr dams to release their bouncing bombs. When this was recreated for the cameras of Associated British in 1954, 60ft actually looked a lot higher on film when the rushes were viewed, so for much of the low-level work Erwin Hillier asked Ken Souter and his team to fly a lot lower, at 40ft.

Later, on at least one occasion, Ken flew low enough over the Derwent reservoir for the downdraught from his Lancaster’s four propellers to draw up individual waterspouts. “I had a few disagreements with Erwin Hillier,” recalls Ken. “He was a bit Teutonic in his manner and wanted us to go lower and I told him straight that it was too bloody dangerous. I also had arguments with the film company about this.” But Erwin Hillier prevailed, and Ken and his team flew their Lancasters at 40ft during much of the filming.

Scenes that re-create 617 Squadron’s training flights in England and Wales before Operation Chastise (the codename for the Dams raid) and the actual operations over the Ruhr dams themselves, were filmed over and along Lake Windermere in the Lake District and the Derwent dam and reservoir in the Derbyshire Peak District. Ken Souter describes something of what was required on camera: “Windermere was quite simple to fly along, but flying across the lake was a different matter altogether. We had to come down a slope then flatten out across the lake and climb up over a mountain on the other side. This was quite hairy because there was not enough power to get up over the other side. I do recall that we got quite a bit of flak from the yachting fraternity on Windermere for our low flying, though! Derwent was just a swoop down between the two towers and not as prolonged as Windermere.”

For Souter, the most difficult part of the filming was when he had to fly through the probing fingers of the searchlight beams as the Lancasters cross the ‘Dutch’ coast: “They put dimmers on the searchlights to lessen the glare for us, but they had to take them off again later for the cameras. Flying into such very bright lights made it very dangerous for us.” Dick Lambert’s signaller, Sgt Bill French, recalls: “It was about 20:15hrs when suddenly there was one hell of a burst of blinding light from the searchlights and the Lancasters and camera aircraft split up and went their own way in great haste. To make matters worse,

Dick Lambert could not see a damn thing because the windscreen was completely smeared in some sort of gunge. Things got rather hairy when there we were, late in the evening with almost zero visibility, nowhere near any airfield to give Dick my assistance in landing the aircraft. In the end he decided to land at Langham to clear up the mess.”

A fair amount of flying activity for the film was conducted from the grass airfield at RAF Kirton-in-Lindsey, Lincs. At the time of the Dams raid in May 1943 Scampton was still a grass airfield, so for reasons of authenticity Kirton was used for filming because its grass runway resembled wartime Scampton.

The one and only formation take-off was filmed at Kirton. Eric Quinney recalls Joe Kmiecik telling him that following this event Kirton’s station commander had withdrawn permission for any further filming of flying sequences because he was not prepared to lose the station’s flight safety record.

“From the moment when the station commander saw our Lancasters turning in to land on his grass airfield he decided there and then that he didn’t want us,” commented Ted Szuwalski. James Fell, who was the air signaller in Joe Kmiecik’s crew, remembers: “The director wanted to film an aircraft flying at the control tower on take-off. This was not possible at Scampton due to the configuration of the runways, so we flew up to Kirton-in-Lindsey where this could be done. After due deliberation, Joe Kmiecik took off towards the control tower and hangars for what was thought to be a good shot, complete with cumulus clouds in the background. Joe’s Lanc narrowly missed the tower and the hangar. His wife who was watching was so upset that she walked off the station in a state of shock. The station commander thought the whole thing was too dangerous and grounded us, banning the Lancasters from any further flying from his airfield. Later, he allowed us one trip out to return to Scampton and told us never to return.”

For the purposes of the film, actor Richard Todd had to be seen starting up and taxying a Lancaster. Ted Szuwalski remembers the occasion on which he helped him: “In the scene where Richard Todd is starting up the engines of his Lancaster before setting out on the raid, it was actually me who started up the Lanc from the right-hand seat with Todd sitting in the left-hand seat. He was holding his hand up to the ground engineer shouting ‘Number one! Number two!’ etcetera out of the cockpit window. I had to be out of sight of the camera so I needed to be down on the cockpit floor to start the engines.”

Once filming had been completed in September 1954, the four Lancasters that had helped to re-create the epic dam busters story were returned to 20 MU at RAF Aston Down, where they languished awhile until declared surplus to requirements. Then, without ceremony, they were cut up and sold to the British Aluminium Co in July 1956 to be melted down for scrap.

Demand for tickets to see the première of The Dam Busters was so great that two Royal Command performances were held in London at the Empire cinema, Leicester Square. The first showing was on 16 May 1955, the 12th anniversary of the raid, and was attended by Princess Margaret. Associated British did not forget the RAF personnel, because they too had their own première when a special preview was shown in the station cinema at Scampton on 20 May. Everyone from Hemswell and Scampton who had been involved in making the film was invited.

The AOC 1 Group, AVM John Whitley, was delighted with the film and the tremendous public relations job it had done for the RAF. “All of us in 1 Group must feel immensely proud that Hemswell, Lindholme and Scampton’s contribution has been a greater factor than any towards its [the film’s] success… I know that this meant a great deal of spare time being sacrificed last summer by both air and ground crews, and that their only reward could be that they were taking part in a picture which might possibly do much to enhance the prestige of the RAF. That this will have been the result of all their good work is now beyond a shadow of a doubt.”