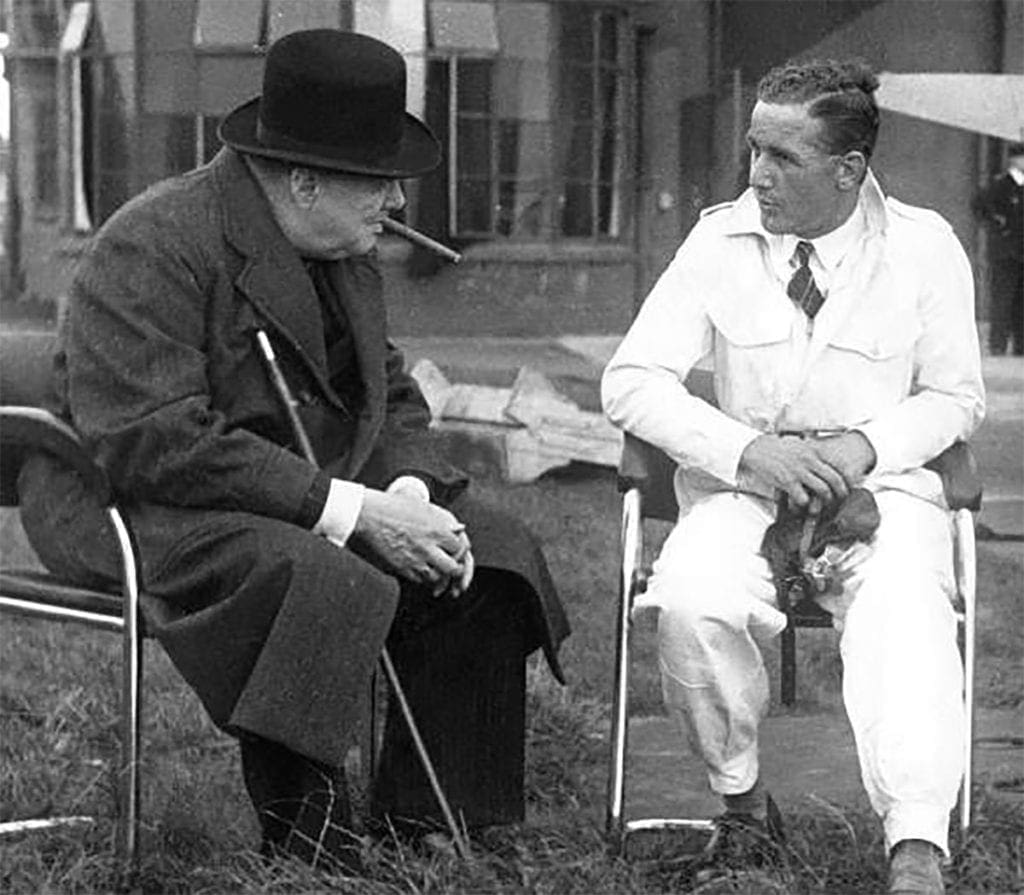

Alex Henshaw was one of the finest pilots of his generation and is best remembered for his work with the Spitfire. François Prins recalls an old friend.

He was typical of the generation of pilots who came to prominence during the inter-war years. As a boy, Alex Henshaw showed a keen interest in motorcycles and aeroplanes, but his father, a successful Lincolnshire businessman, thought that aircraft were less dangerous than motorcycles and, in 1932, paid for Alex to learn to fly at the Skegness and East Lincolnshire Aero Club. He was a natural pilot and quickly flew solo.

To mark this achievement, his father gave him de Havilland Gipsy Moth I G-AALN. “It was a marvellous aircraft, and we had some fun with that,” recalled Alex. “My father and I used to fly around and he became fascinated by flying and soon learned himself.” Alex Henshaw was born in Peterborough on 7 November 1912, and was educated at Lincoln Grammar School. He joined his father’s business, which included farm supply and land management. Alex enjoyed the work: “It taught me a great deal about people and how to get the best out of them. I only went out on the road as a holiday job after leaving school, but became good at it and enjoyed the challenge.” Although a novice pilot, Alex felt competent enough to enter the 1933 King’s Cup Air Race as one of the youngest-ever

Alex… would sometimes test 20 or more aircraft a day whatever the weather.”

However, it was in the King’s Cup Air Race of 1935 that Alex nearly came to grief. He had entered his new Miles Hawk Major G-ADNJ and was crossing the Irish Sea which was part of the route. He takes up the story: “Suddenly, there was a loud crack and the prop flew away, flickering in the brilliant sunshine as it disappeared in the depths below. The engine screamed like a demented banshee and clouds of acrid smoke poured from the cowlings before I could snap the throttle closed.” Alex did not panic and looked for a ship, he spotted the Manx Queen and ditched the aircraft almost alongside. He was dismayed as he watched it steam off into the distance. “I thought, they’ve left me to drown. Of course, I later realised that you cannot just stop a ship, it takes quite a time to come to a standstill. I was pleased to see them lower a boat and I was soon on board.”

Later, in November 1935, Alex had to bale out when his Arrow Active biplane G-ABIX burst into flames. As he floated down the“…blazing inferno passed under my feet, so close that I could hear the flames crackle and roar like a power-driven forge and I could smell the smoke as I drifted silently through it.”

In 1938, Alex entered his new Percival Mew Gull G-AEXF racing aeroplane for the King’s Cup and set an average speed of 236.25mph, a record that stands nearly 70 years later and is unlikely to be beaten. Another record that was only broken in 2009, was Alex’s solo flight from Britain to Cape Town and back. He took off on 5 February 1939, in his Mew Gull, and flew non-stop to Oran in Algeria to refuel. He reached Cape Town, having flown 6030 miles 40 hours after leaving Gravesend. After a day’s rest he set off from Cape Town to return to the UK and landed at Gravesend on 9 February, four days, ten hours and 16 minutes after departure.

Having completed one of the greatest ever solo long distance flights he was totally exhausted and had to be lifted out of the cockpit. Alex had broken the return record, established in a twin-engine aircraft flown by two pilots, by seven hours and the out-and- return time by almost 31 hours.

SUPERMARINE INVITATION

When war was declared on 3 September 1939, Alex immediately volunteered for RAF service. While waiting for his application to be processed he was invited to join Vickers- Armstrong at Weybridge as a test pilot. Initially, he test-flew Wellington and Walr us aircraft. What really frustrated him was the office politics and lack of flying. “I was fed up and was about to leave when Jeffrey Quill, the chief test pilot of Supermarine came into my office. He said, ‘Alex Henshaw? I’m Jeffrey Quill and I hear that you are leaving. Why don’t you come and help me at Supermarine, we have a lot of work to do.”

Skew-gear of the Rolls-Royce Merlin nearly claimed his life. On one occasion, having lost all power, he crash-landed a Spitfire near two rows of houses, the wings of his aircraft sheared off, and the engine and propeller finished up on someone’s kitchen table. Alex was unhurt and was left sitting in the small cockpit section, which fortunately remained intact. Another time the engine of a Mk.IX seized and the aircraft began to vibrate uncontrollably; Alex was thrown out and took to his parachute, only to discover that three of the silk panels were missing, but it held together and Alex landed safely.

TESTING 20 SPITFIRES A DAY

At its peak, Castle Bromwich was producing 320 Spitfires each month and test flying had to continue whatever the weather. Alex authorised himself to fly in adverse conditions, as he had worked out his own method of taking off and landing in bad weather. He would look for the plume of steam from the cooling towers of the nearby Ham Hall power station. This gave him the co-ordinates for the airfield; it never failed and meant that he was flying when no one else could. Alex was able to keep up with production and would sometimes test 20 or more aircraft a day whatever the weather.

Castle Bromwich had become the largest aircraft manufacturing base in the UK for the Spitfire and had also become a major producer of the Avro Lancaster heavy bomber, which Alex also tested. Between 1940 and 1945 he test flew some 2360 individual Spitfires and Seafires, amounting to around 10 per cent of the total build.

Although he retired from flying in 1948, he never lost his love for aircraft, especially the Spitfire. Alex once told me: “It was a delight and once you got to know the aircraft it was easy to fly and you could make it do anything you wanted.” Happily, Alex was able to fly in a two-seat Spitfire in more recent times at a private event in 2005. Once airborne, he took the controls and put on a stunning display. His son, Alex, told me that he had never seen his father fly a Spitfire before that day. Alex showed that he had not lost any of the flair that made his flying stand out. A few months later, to mark the 70th anniversary of the first flight of the Spitfire in March 2006, he flew over Southampton in the same two-seat Spitfire and, once airborne, took the controls again.

Alex never looked back and was always thinking about what he still had to do. I last saw him the day before he died (24 February 2007) and we talked about two projects that were in the pipeline. Both have come to fruition; the first is a book of paintings by Michael Turner with text by Alex and photographs from his illustrious flying career. The other is the relocation of the Henshaw archives – including the many trophies that he won – at the Royal Air Force Museum London. Alex paid for a full-time curator to catalogue the collection and commissioned a full-size replica of the famous Mew Gull; the latter is now on display in the Milestones of Flight gallery. Alex may have gone, but his spirit lives on and wherever there is a Spitfire flying, one will always think of him. I was fortunate and honoured to be able to call Alex my friend; every moment spent in his company was a delight. He was quite simply a remarkable man.